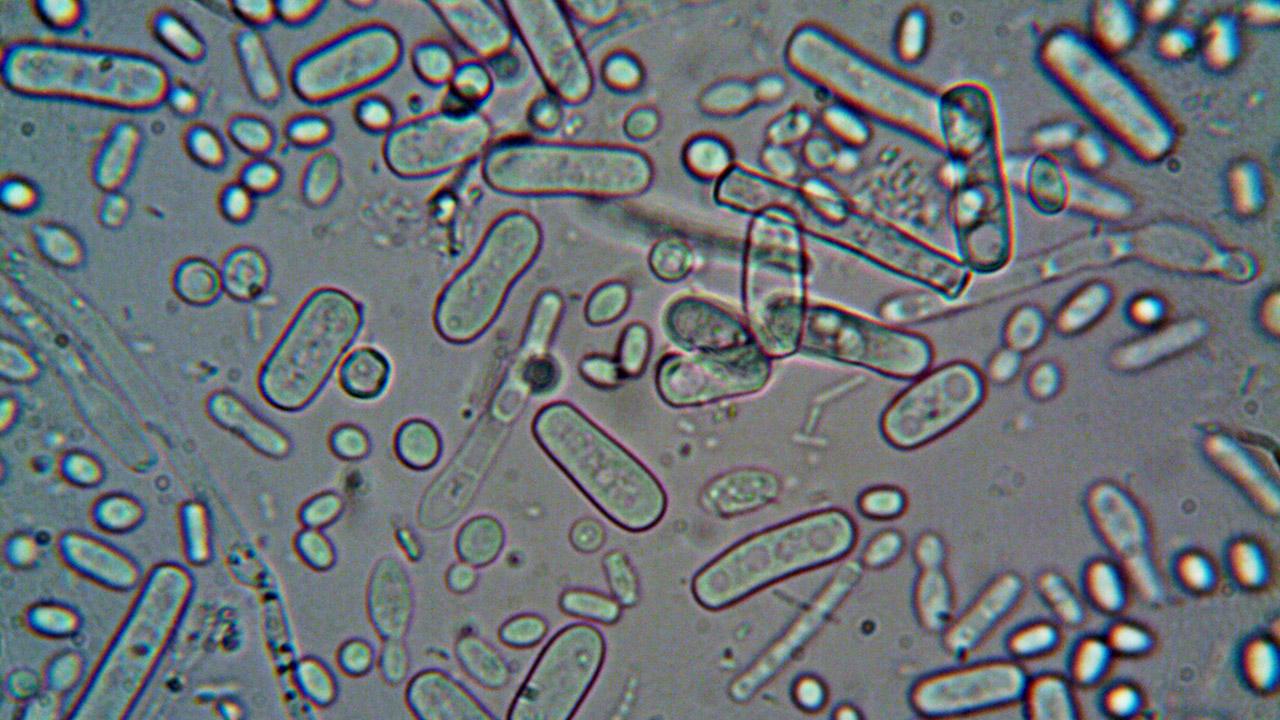

Every day, we rely on our ability to remember patterns and associations to help us prepare for future events. We might expect rain on a cloudy day, and choose to take the bus rather than bike. Although learning and adaptation are typically associated with complex organisms, research has shown that even the simplest life forms—like bacteria—demonstrate a striking capacity to anticipate future changes. So how do they do that? This is what ICTP research scientist Jacopo Grilli and his collaborators at Yale University and at the Tokyo Institute of Technology set out to investigate, thanks to a new grant from the Human Frontier Science Program.

Grilli offers an example: “Take E. coli. A population of this well-known bacterium experiences regular cycles. It goes from grass to the mouth and then gut of an animal, where the bacteria reproduce before being excreted and returning to the soil,” he continues, adding, “It has been observed that when E. coli experiences a shift to higher temperatures --- similar to an animal body temperature, it expresses proteins essential to its survival in an anaerobic environment, as if in preparations for the lack of oxygen in the animal gut.”

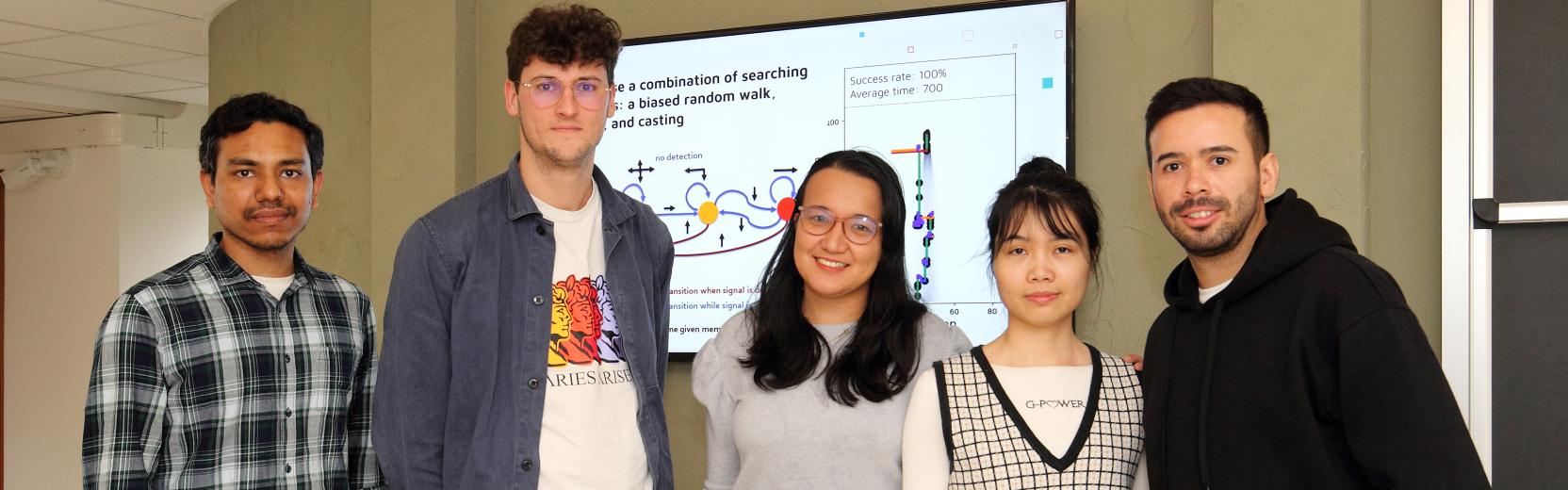

Grilli, who works in the ICTP Quantitative Life Sciences section and uses statistical models to describe the behavior of biological systems, has teamed up with Martina Dal Bello, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale University, and Shawn McGlynn, an associate professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology specialising in microbial biogeochemistry, to investigate exactly how bacterial populations learn to anticipate environmental changes.

Dal Bello and her team will perform experiments where bacteria will be exposed to carefully controlled sequences of different environmental conditions. “What they want to see is whether the bacteria will start anticipating the changes that occur most consistently. If so, we expect the population to eventually express features indicating the future they expect,” Grilli explains.

The team will combine observations on bacteria populations with single-cell experiments performed in Japan by McGlynn’s group. “We want to understand whether the population adapts by optimizing the characteristics of all individuals—something that could be very risky if things do not go as expected—or rather prepare for a range of possible scenarios by increasing the heterogeneity of the group, which could increase the survival of the population when the future is very unpredictable,” Grilli continues.

By combining mathematical models with evolutionary and single-cell experiments, the group seeks to develop a general understanding of learning mechanisms and their limits across the microbial world.

As required by the Human Frontier Sciences Program, which fosters international, interdisciplinary collaborations in the life sciences, Grilli, Dal Bello, and McGlynn have never worked together before and none had previously tackled this particular problem. They met at conferences and workshops organized by ICTP and have just embarked on a journey through the fascinating world of bacteria. They hope to be joined by PhD students and postdocs interested in participating in this cross-continental collaboration.

Visit this page to learn more and explore open positions.