“Scientific thought and its creation are the common and shared heritage of humankind,” ICTP founder Abdus Salam once said – and over the years, ICTP has been home to scientists from different backgrounds, encouraging their contributions to science irrespective of the geographical, economic and gender-related factors that often hinder their advancement in academia. Success is often depicted as a linear path—starting with a PhD, followed by one or more postdoctoral positions, publishing in top journals, securing grants, and meeting institutional expectations. But such a linear way forward is the privilege of a few; for most, the journey is filled with twists, turns and obstacles. At ICTP, these unconventional paths are celebrated as vital contributions to the pursuit of knowledge.

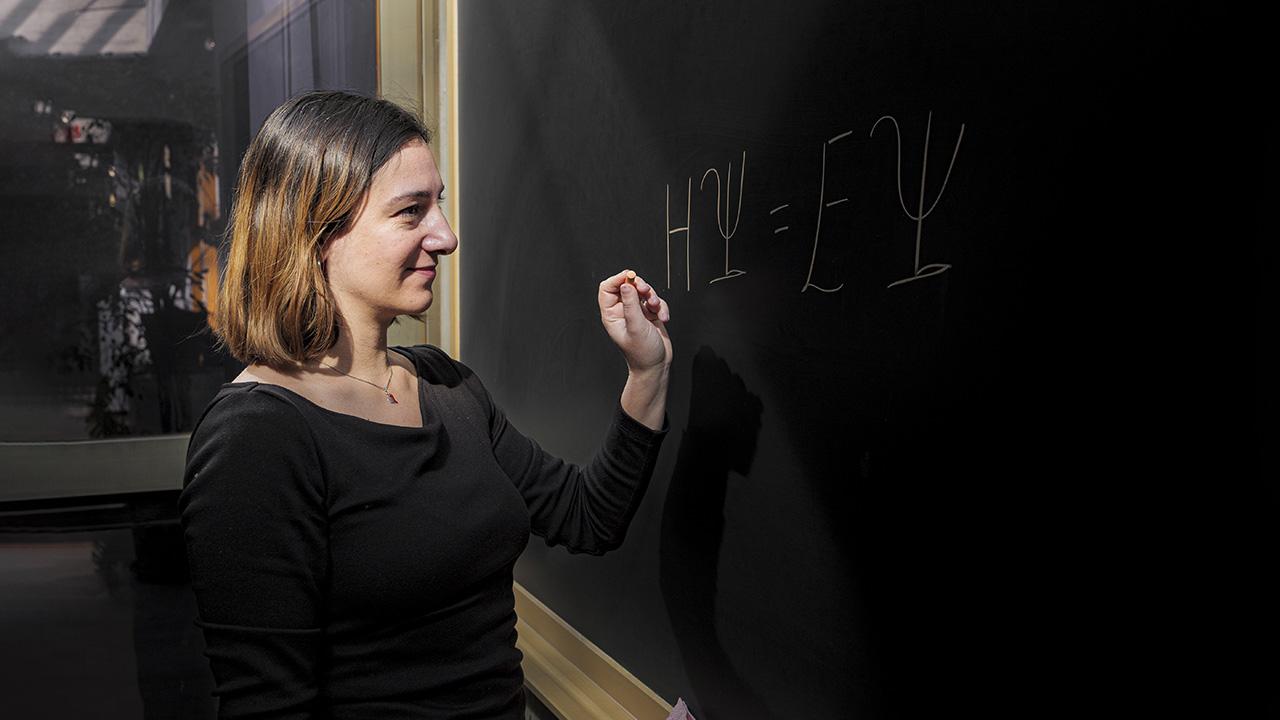

Martina Stella, a senior research scientist at the quantum-computing start-up Algorithmiq and a long-term visiting scientist in ICTP’s Condensed Matter and Statistical Physics (CMSP) section, found her way in science by following her interest across multiple research fields. Her career path did not follow the conventional academic trajectory that she was advised to take. Instead, by following her passion, she found a career that truly reflects her interests and her values.

If you have a vision of who you want to be, there are many ways to get there, even though many people will tell you that there is only one way forward.

What is your current role at ICTP and at Algorithmiq?

I have a double position as a long-term visiting researcher at ICTP, and as a senior research scientist at Algorithmiq, a Finnish start-up company that specialises in finding quantum computing solutions for problems in applied sciences. This means that I develop my own independent research, and as the start-up grows I will be able to develop my own research group. At the same time, I can keep on collaborating with ICTP and support its mission, by teaching in the Diploma Programme for example and taking part in other activities organised by ICTP, compatibly with my role at Algorithmiq. I wanted to work in academia and in many ways I do exactly what I wanted to, but my career did not follow a straight line and I had to be creative about it. I would like to pass this message on to the aspiring young researchers out there, especially in the ICTP community. If you have a vision of who you want to be, there are many ways to get there, even though many people will tell you that there is only one way forward.

Following my curiosity, I developed a broad skill set in theoretical and computational chemistry, moving across different institutions and collaborating with various groups.

You say that your career path was not straight. How so?

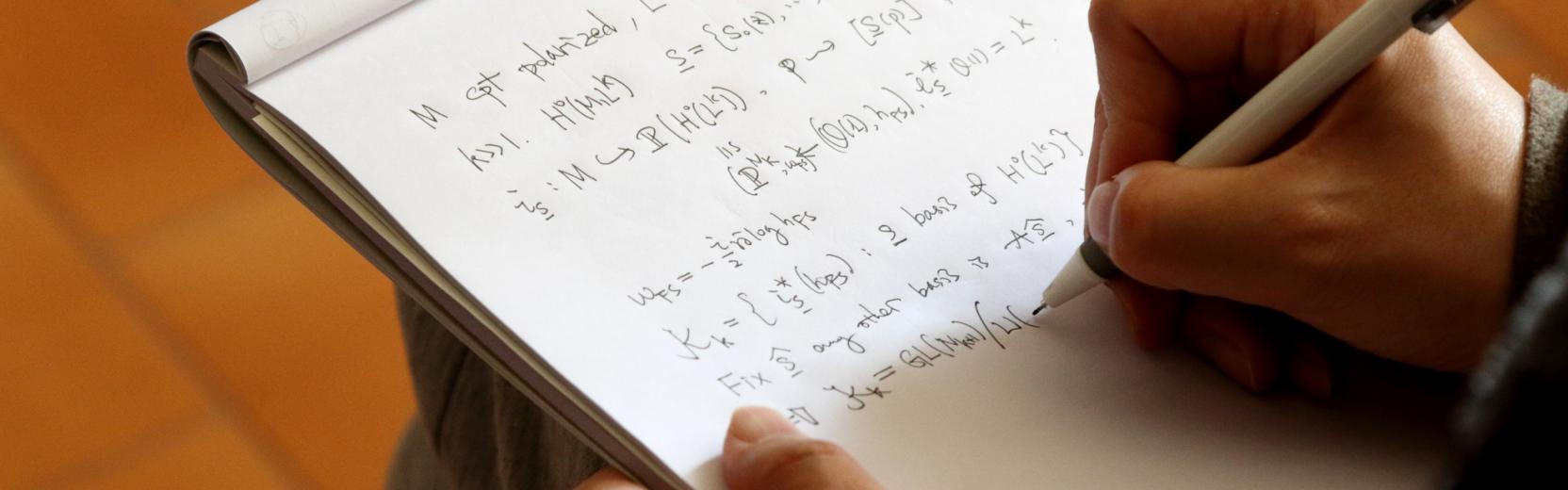

Although academia—especially in Italy—often values specialisation, my path was different. Following my curiosity, I developed a broad skill set in theoretical and computational chemistry, moving across different institutions and collaborating with various groups. I did my bachelor’s degree in chemistry at the University of Naples, which is where I am from, and soon found out that what I liked the most was the quantum interpretation of chemistry, and for my final bachelor’s project I chose to work on investigating theoretically the structural features of proteins relevant in neurodegenerative diseases. I left Naples early for a master’s project at Cambridge, then pursued a PhD at Bristol in the development of methods for modelling the electronic structure of molecules. I was very lucky to very quickly publish my first paper. Seeking a postdoc position in a new city, I moved to London, where I worked on a pioneering machine-learning-driven platform for material data sharing—a very exciting adventure that helped me develop many soft skills and a broad network of contacts, but gave me very few opportunities to publish. This left me without a clear academic identity—I was no longer a pure theoretical chemist, but not a materials scientist either. Because of that and without the encouragement that many male colleagues receive at that stage of their careers to apply for independent fellowships, I took another postdoc at Imperial College London, shifting back focus on electronic structure but this time of very large molecules. That was supposed to be a cornerstone in my career, but my father’s illness, followed by the pandemic, meant that I could not progress as fast as I would have wanted to. As I searched for my next step, ICTP came into the picture.

How did you arrive at ICTP?

When the time came to look for a new position, I was not sure whether I was ready to apply for an independent fellowship or if I had to consider doing another postdoc. That is when I saw some fellowship opportunities advertised by ICTP, and I decided to apply. The whole selection process was very quick and I was soon offered the position in the CMSP section. Here they gave me the opportunity to do my independent work, which was very important for me at that point. One year later I won ICTP's Boltzmann fellowship, which was a more senior and more independent position. When that happened I felt that my dream career in academia was back on track. I was and still am very enthusiastic about ICTP’s mission which gave me the opportunity to share knowledge and interact with students and collaborators coming from all over the world. Then I was offered the opportunity to join Algorithmiq.

Quantum computers do exist and there are increasingly many. However, quantum technology is not perfect yet and quantum computers still make important mistakes.

How did you end up working for Algorithmiq?

Although my position here at ICTP was good by then, and I was progressing as an academic, I was still feeling that the numbers that are supposed to define my career had not grown as steeply as they Italian system would generally consider appropriate. Moreover, I had been out of the Italian academia for too long and lost most of my connection with local networks. ICTP, being more open and international, was an ideal and welcoming way forward for me.

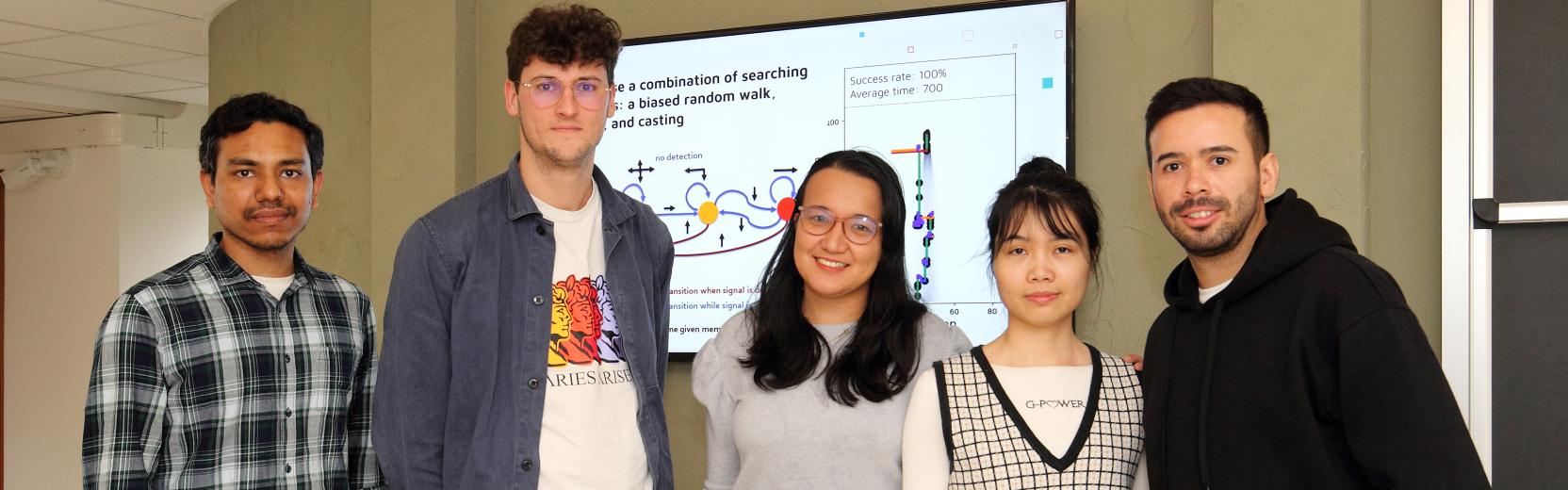

During my time as a Boltzmann fellow, I was asked to organise seminars for the CMSP section and the list of invited speakers included Prof. Sabrina Maniscalco, who was working on applications of quantum computing for life sciences and chemistry. I was chairing her seminar and I ended up asking her many questions, which is something I do not usually do. She immediately recognised my background in chemistry, and particularly in quantum chemistry, and proposed that I join the start-up that she was launching, Algorithmiq. There were many positive aspects about it–especially that people there were working on further developing the method that I had developed during my PhD. I would also have been able to work for them all the while staying in Trieste, and they were giving me the opportunity to develop my own research group. It sounded great, but I wanted to keep working for ICTP. This hybrid situation, in which I work full-time for Algorithmiq but at the same time participate in ICTP’s mission is the solution we found and I am happy about it.

What do you work on at Algorithmiq?

My role at the start-up is to identify systems – mainly biological, but also technology-oriented – that quantum computers could model more efficiently than current technologies allow. Essentially, I am looking for candidate problems that can help us test and make optimal use of existing quantum computers.

I do that by studying these systems with classical computers, in order to identify their specific limitations. Because resources are limited and can be expensive , we choose our case studies very carefully, among the projects that we think will have a higher impact and will help us show that quantum computing can be a game-changer.

Once we identify a strong candidate project to be studied on quantum computers, for example a certain biomolecule, we need to model it on a quantum computer. We have a whole team working on that, but what I can do and would like to learn is to “translate it” into a format that quantum computers can understand. This means going from a fermionic format – a wave function – to a circuit, that a quantum computer can process.

So quantum computers are actually out there and can already be used?

Quantum computers do exist and there are increasingly many. However, quantum technology is not perfect yet and work needs to be done to understand and correct the errors they make. There are currently two main approaches to quantum computing. On one hand, some researchers and companies prefer to work towards perfecting the current technology before they start applying quantum computers. On the other hand, at Algorithmiq we rather develop quantum software that optimises most of the aspects of current quantum computation, to make the most of the technology that already exists. This means, for example, that in order to meaningfully compare what we get from a quantum computer with the output of classical ones, we need to process the output in order to deal with the errors that are intrinsic to current technology.

I want to foster an environment where everyone—regardless of background, gender, or personal inclinations -- feels welcomed and encouraged to express their ideas.

What would you like to say to a young student who dreams of becoming a scientist?

I hope that my story will be an example for them. I would like to show them that there are many possible ways to do a job that you like. ICTP’s environment is great for that and I think that my story fits well with this institute. Young researchers who come here often have not had the possibility to develop their careers according to the rigid criteria of Western universities. I also hope that little by little we can change the academic system and make it more flexible. I want to foster an environment where everyone—regardless of background, gender, or personal inclinations -- feels welcomed and encouraged to express their ideas.