Ten years might sound like a very long time, but in the time frame of basic scientific research, it can be quite short – especially when that is the time it takes to see one’s theoretical predictions verified experimentally. So when last summer Yanier Crespo discovered that the simulations he had done a decade ago while he was a young PhD student at ICTP and SISSA had just been proved by observations, he was pleasantly surprised.

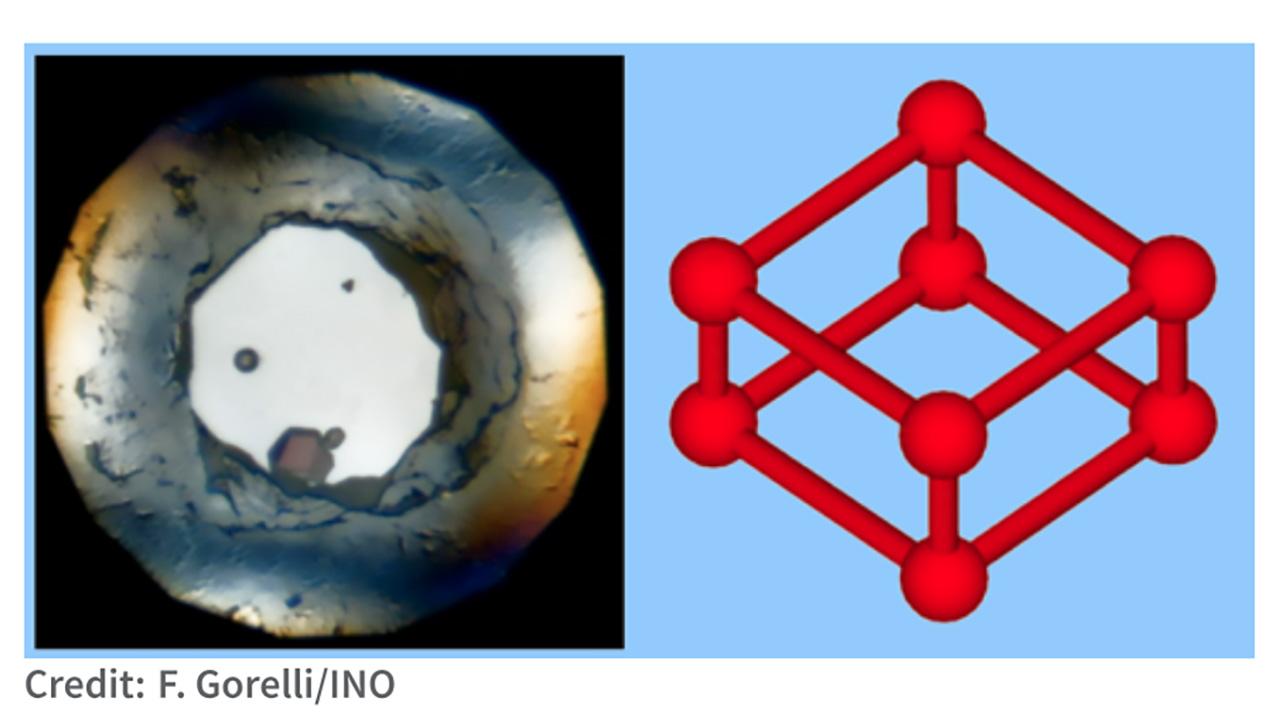

The experiments were performed at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, and they used advanced X-ray methods to study the microscopic structure of oxygen under extreme pressure. The analysis revealed a change in structure corresponding to the phase transition predicted by Crespo in 2014, in collaboration with Erio Tosatti and Michele Fabrizio at SISSA, and Sandro Scandolo at ICTP.

“Oxygen is a very special element,” says Tosatti, who is now professor emeritus at SISSA and a scientific consultant in ICTP’s Condensed Matter and Statistical Physics section. “Not just because of its importance for life, and its major role in chemistry. Even a single O2 molecule is peculiar, as it carries a magnetic moment, something quite unusual for a neutral stable molecule. Exactly 100 years ago, explaining the mysterious O2’s magnetic state helped Lennard-Jones to convince a very skeptical chemical community that quantum mechanics worked and was important,” he explains smiling.

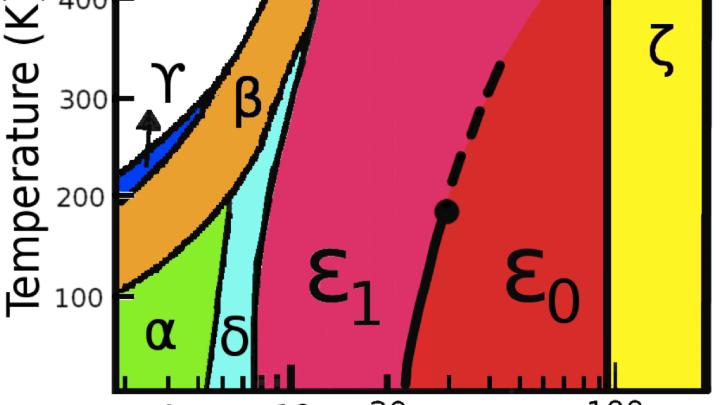

Oxygen’s magnetic state is also very robust across most of its phase diagram. “When, under increasing pressure, oxygen is condensed to a gas, then to a liquid, then squeezed into various solid phases, the molecular magnetic moments persist. Things, however, change at about 8 GPa, above which magnetism apparently disappears, and a vast nonmagnetic phase called “epsilon” begins, uninterrupted up to 96 GPa, almost a million times the pressure of the atmosphere. In this epsilon phase the molecules bizarrely form groups of four”, Tosatti recounts.

Well explained as these quartets were by conventional calculations that neglected magnetic effects, for a long time it remained nonetheless unclear whether molecular magnetic moments – or spins – still played a role in the epsilon phase. That is precisely what Crespo’s first-principles simulations helped clarify. In an article published in 2014 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), he and his collaborators predicted that the epsilon phase in reality consists of two phases, one in the higher pressure range, between 18 and 96 GPa, and another one arising at lower pressures. While the former was indeed characterised by the absence of molecular magnetic moments, simulations and calculations showed that at lower pressures, between 8 and 18 GPa, a different strongly correlated phase prevails, where the molecular magnetic moments are still present, but their overall magnetic ordering is prevented by a dynamic resonance phenomenon inside each O2 quartet.

“What I think is most interesting about our result is that we predicted that the lower-pressure phase would behave like an exotic quantum state akin to a spin liquid. That is a kind of state which, in other contexts, theoreticians have been working at for a long time, and that is both important and rare in nature. The fact that this has now been proven by experiments could be a breakthrough to study newer types of spin liquids experimentally,” says Crespo, who now works as an IT consultant for a company in Trieste. “Seeing that our theoretical predictions have been verified experimentally means a lot to me. It shows that I was able to leave a mark in science. Because I left research about ten years ago, this also signifies that I can close that chapter of my life with the best possible result and that gives me deep satisfaction,” he comments.

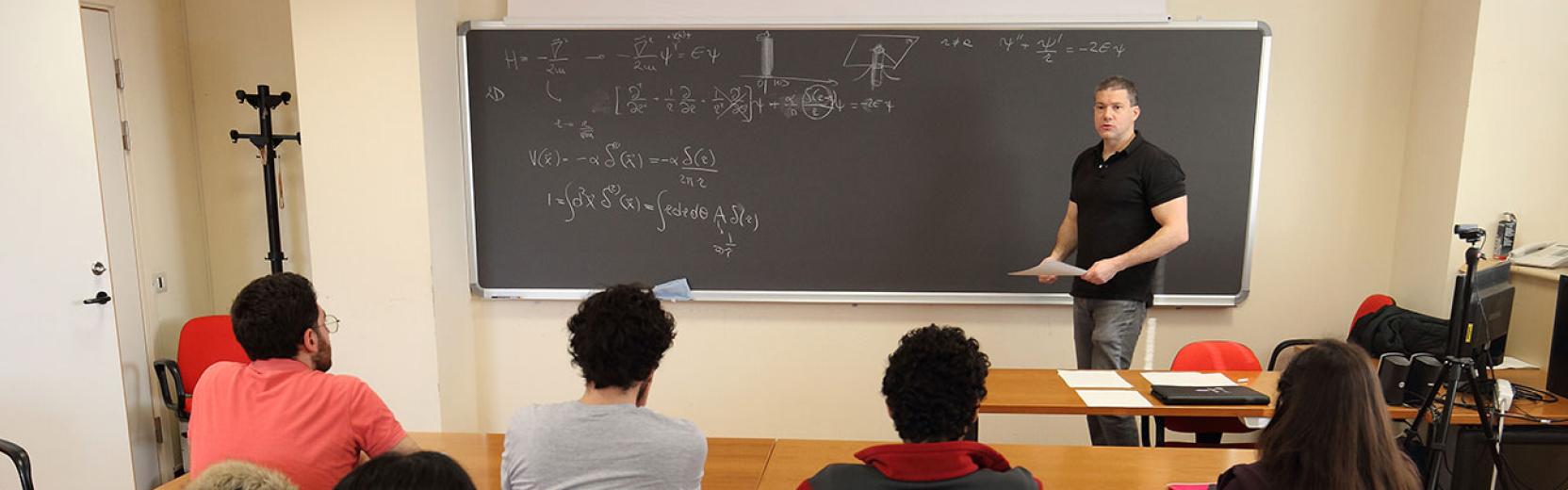

Crespo, who is originally from Cuba, had arrived in Trieste to attend the ICTP Postgraduate Diploma Programme, and then stayed to do a PhD and then a postdoc. “Being part of that programme was like living a dream. It was wonderful to attend the lectures of professors like Sandro Scandolo and Giuseppe Santoro, and to be in contact with my main supervisor Erio Tosatti,” he says, adding, “ICTP and SISSA, and all the professors I met there, have changed my life in a very good way and I want to thank them for that,” he concludes.