Nuclear fusion is the reaction that powers the Sun. In the fusion process, hydrogen nuclei bump into each other and merge, thus producing helium nuclei and releasing energy. Harnessing fusion on Earth holds the promise of clean, wasteless, and effectively unlimited energy, but has proven to be incredibly challenging. It requires confining a plasma of hydrogen ions – deuterium and tritium being the favorite candidates – at temperatures higher than 100 million degrees Celsius. Only at such high temperatures can the nuclei come close enough to overcome their electric repulsion and be brought together by the strong interaction.

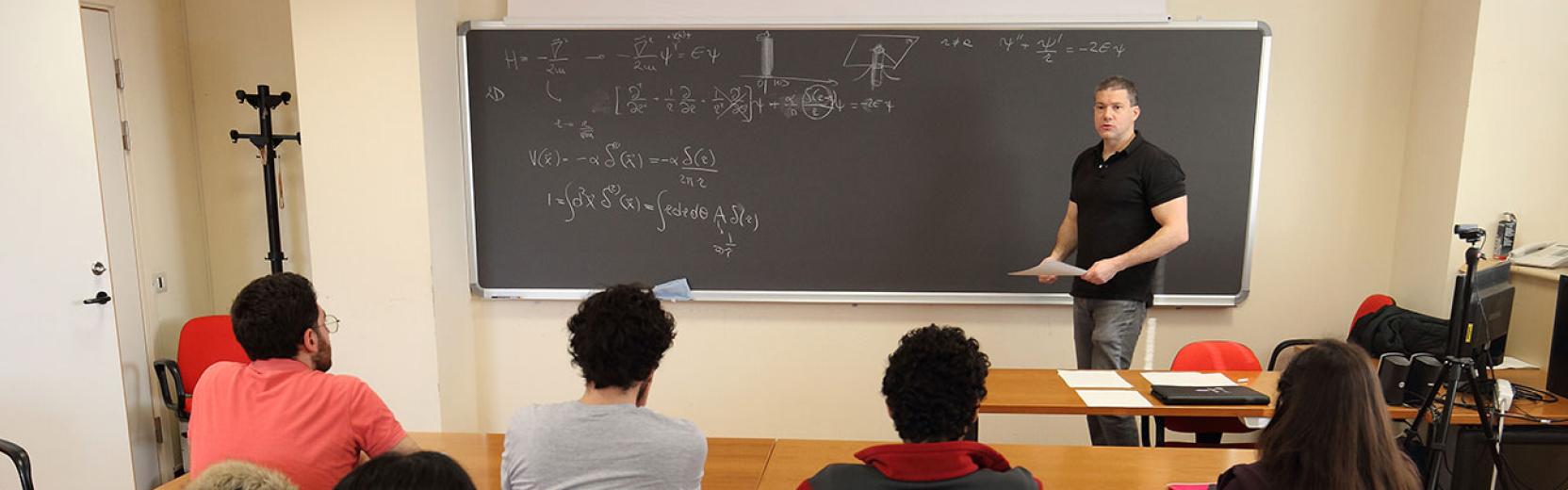

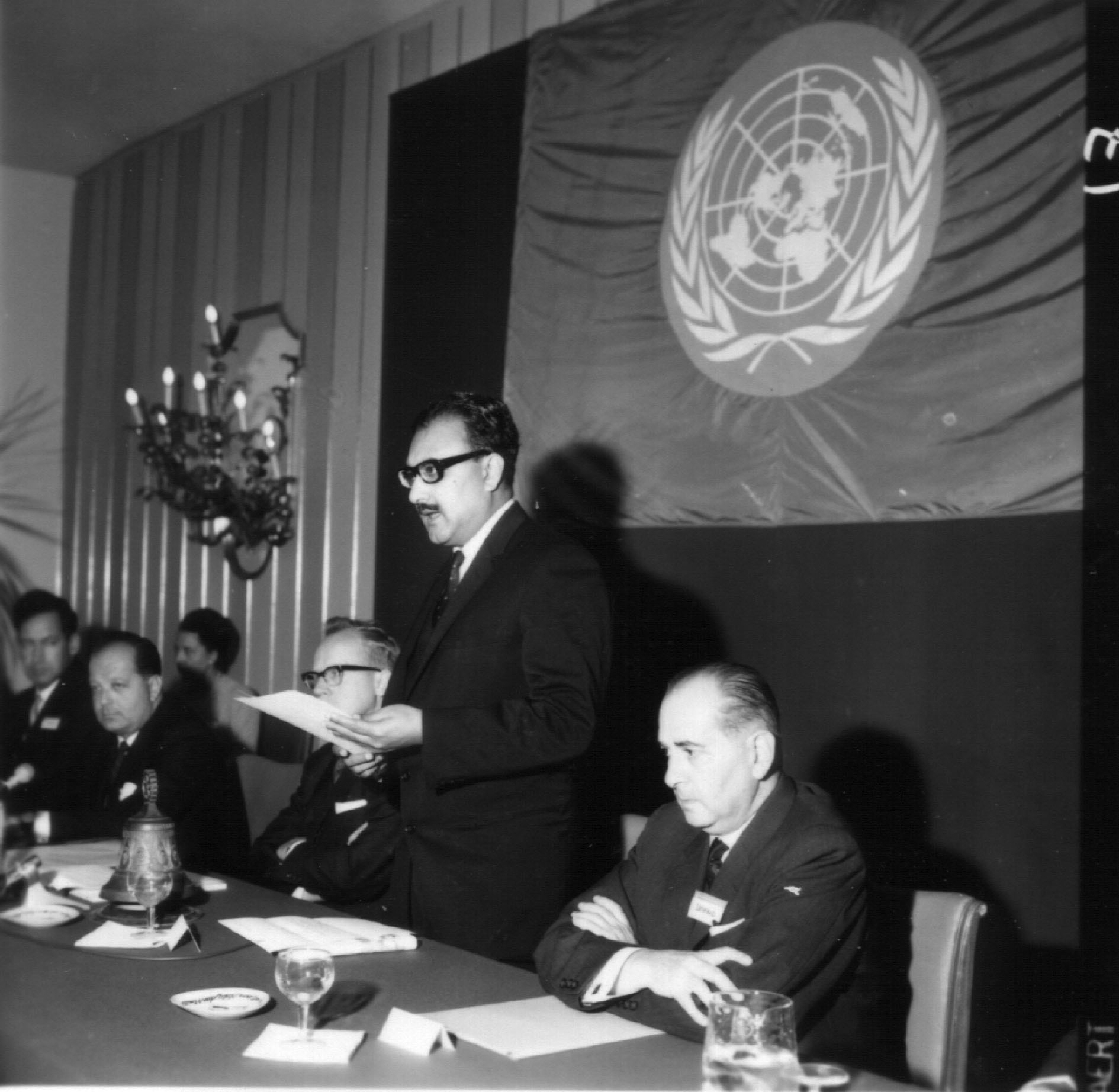

Research into fusion as a possible source of clean power started in the mid 1950s and 60 years ago, from 5 to 31 October 1964, ICTP and the International Agency for Atomic Energy (IAEA) organized the very first international workshop on plasma physics and controlled fusion at ICTP. The opening ceremony of the conference, which took place in Trieste, also marked the inauguration of ICTP.

A picture from the ICTP archives shows the then ICTP Director Abdus Salam as he addresses the audience at Hotel Jolly in Trieste. The patronage of the United Nations, whose emblem stands behind Salam, meant that scientists from countries on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain could attend. “In bringing together plasma physicists belonging to three distinct schools, the American, West European and the Soviet schools, the Seminar provided a unique opportunity for extended contacts between physicists in this field,” the proceedings of the conference recount.

“That first workshop in 1964 was a major event, not only in the history of ICTP, but in the history of plasma physics. All the luminaries in the field took part in that school, including Boris Kadomtsev from the Soviet Union, and Marshall Rosenbluth, from the United States,” explains Swadesh Mahajan, Research Professor at the University of Texas and one of the historical directors of the ICTP-IAEA joint Plasma Physics School, that starting in 2024 turned its name into “Fusion Energy School”.

Almost every plasma physicist in the developing world was trained by the joint ICTP-IAEA school over the years.

-- Swadesh Mahajan, Research Professor at the University of Texas

As the Centre is celebrating its 60 anniversary this year, so are ICTP and the IAEA’s joint efforts to train scientists to the challenges of controlled fusion, which have continued over the years through regular schools, organized every year or every second year.

Mahajan was asked by Rosenbluth himself to direct the school in 1987 and he has continued to do that since. “Almost every plasma physicist in the developing world was trained by the joint ICTP-IAEA school over the years. Plasma physicists in Argentina, Chile, India, Pakistan and Iran have all be trained here in Trieste and we have an unblemished record of welcoming the most talented young researchers and turning them into scientists of repute,” he continues.

Since 1964, important progress has been made and research into fusion is now entering an exciting new era. That the final line to achieving the goal of net energy gain through fusion now looks closer and closer is shown by the increasingly large number of companies that are investing in the field.

“Fusion is now in the near future,” says Ralf Kaiser, Senior Coordinator of Programmes and Advancement at ICTP, also a director of the joint ICTP-IAEA Fusion Energy School. “Developing countries are where fusion energy plants will have the potential to make a real difference in the future,” explains Kaiser, who is former Head of the Physics Section at the IAEA, where he was responsible for the IAEA programmes on nuclear fusion. “Countries such as India, Indonesia, Nigeria are going to need much more energy in the next 20 to 30 years. Coal power plants being cheap and easy to build, the temptation will be high to install new ones in order to secure energy supplies. This however would come at a huge environmental cost, as coal is responsible for large greenhouse gas emissions and is a key contributor to climate change,” he explains.

Developing countries are where fusion energy plants will have the potential to make a real difference in the future.

-- Ralf Kaiser, Senior Coordinator of Programmes and Advancement at ICTP

“Fusion has many advantages compared to coal: not only does it not require much space, but also and most importantly, once we become capable to use it at a large scale, it will provide us with effectively limitless, clean and safe energy,” Kaiser continues. In order for this sophisticated technology to become a viable and sustainable option for countries, including developing ones, however, there needs to be a local capacity of knowledge and skills that these countries can rely on. “Even in a scenario where a country decides to import fusion power plants, it will only be able to sustain it over the long term if locally it can count on people who know what fusion power plants do and how they work. Moreover, governments will need to rely on knowledgeable advisors for their decision making,” he explains.

This underlines the importance of ICTP’s and the IAEA’s joint efforts to train scientists, especially from the global south, in fusion energy. With more than 60% of participants coming from developing countries, including India, Brazil, Iran, Pakistan, Indonesia and Costa Rica, just to mention a few, over the past 60 years the joint ICTP-IAEA schools have been contributing to building capacity for fusion energy in developing countries. “With the ascendance of fusion, my hope is that the school will gain greater amplitude and will attract even more participants from across the world who will benefit from the expertise of the international experts that every second year come to Trieste to pass their knowledge on to future generations of researches,” Mahajan concludes.