ICTP has been celebrating its 60th anniversary this year with scientific conferences, international symposia, schools and public science talks that have been taking place throughout the year, and across four different continents.

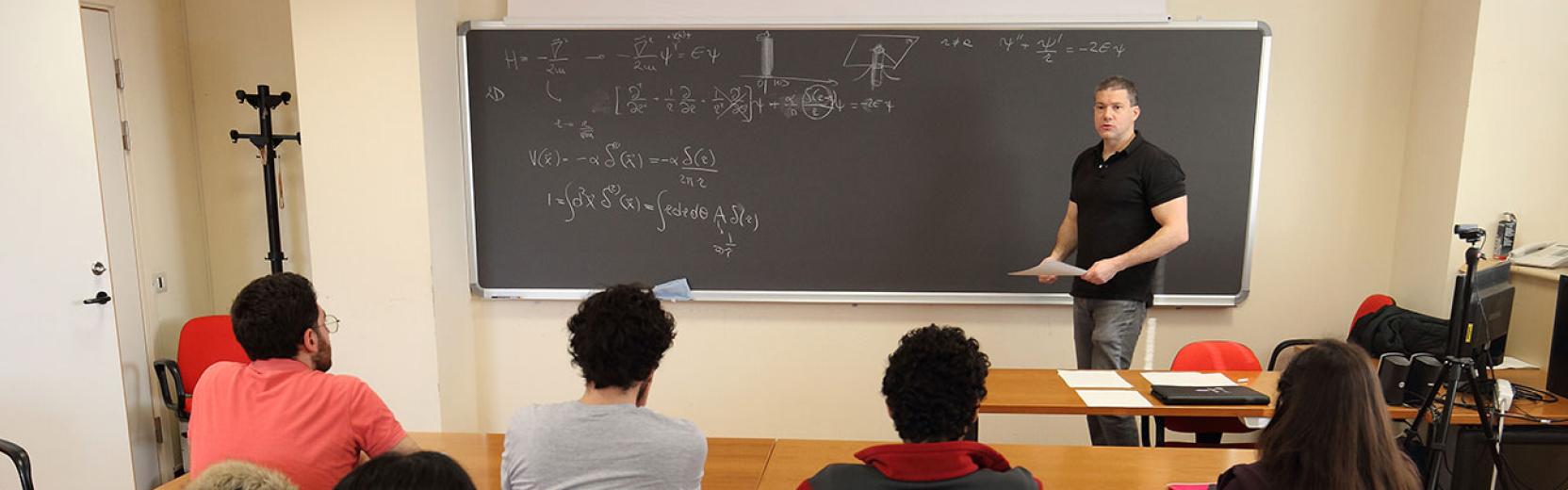

One such anniversary event took place in early November, when ICTP’s Quantitative Life Science section organised a Hands-On Quantitative Biology School in Havana, Cuba, in collaboration with the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology and the University of Havana, where the school took place. This two-week event aimed to expose biology and physics PhD students and postdocs to quantitative and interdisciplinary approaches in biology, with a combination of theoretical lectures and experiments.

“The integration of physical, mathematical, and life sciences has proven to be a very successful avenue for deepening our understanding of biological systems,” explains ICTP researcher Jacopo Grilli, an organiser of the school.

The school's hands-on activities were inspired by the research of physicist Max Delbrück and biologist Salvatore Luria, who were awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

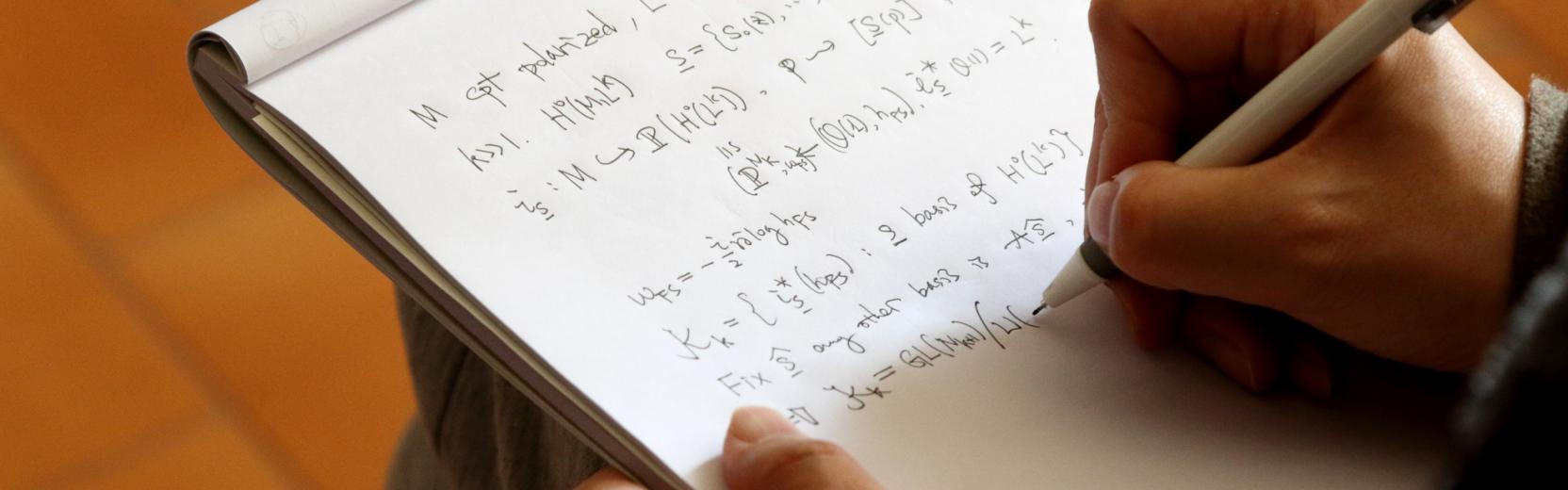

Experiments carried out by Delbrück and Luria in the 1930s solved a controversial debate in evolutionary biology and showed that mutations are spontaneous, as initially hypothesised by Darwin. That experiment was recreated by one group of students at the school using yeast; other groups worked on the properties of bacterial growth, studying how they interact, how they move, and how they change the environment. Further experiments investigated how a biofluid travels in the free space and inside a human nasal cavity model, as well as a bioacoustics analysis of the sound of Cuban frogs.

The hands-on experiments proceeded in spite of Cuba's ongoing nationwide electricity blackouts that made the school's logistics challenging. On top of that, the arrival of Hurricane Rafael during the first week of the school required a tumultuous reorganisation of the programme “Thanks to the hard work of the lecturers and the local organizers -- Prof. Roberto Mulet and Prof. Ernesto Altshuler -- and to the enthusiasm of the students, the courses could resume by the end of the first week, and the event was actually very successful,” Grilli explains, adding, "Paradoxically, the challenging conditions are what made the school impactful. They are what, on the long term, produce the isolation experienced by Cuban scientists. Not many institutions, other than ICTP, would put effort and resources in organising an activity in such challenging conditions."

The school was designed to expose a diverse group of students to a very interdisciplinary environment, requiring a collaboration between different faculties and institutions to make the event a success. “Thanks to the efforts of all people involved, the students learned how to collaborate hand in hand across disciplines, and directly experienced how the quantitative approach of physics allows for asking and answering deep questions in life sciences,” Grilli continues.

“Exposing students to the power and challenges of interdisciplinary collaborations at an early stage of their careers will contribute to creating a new generation of scientists capable of asking and answering novel, big questions in both physics and life sciences,” Grilli concludes.

Photos from the school are available on ICTP's Flickr page.