Predicting what will happen in a chaotic system is a tricky endeavour. Yet the twenty mathematical scholars who gathered at ICTP from July 21 to August 2 are taking on the challenge.

"It's well known that it is not possible to forecast the behavior of the future in an efficient way, and numerical error plays an important role in preventing long-term forecasting," explained Stefano Galatolo of the University of Pisa, who organised the conference with local organizer Stefano Luzzatto of ICTP. "But still there are quantities, related to the statistical behavior of the future, which are in some sense stable and in principle forecastable. It becomes important to understand if these quantities which are quite abstract and complex are computable from the knowledge of the system."

Computer-assisted proofs and techniques in dynamical systems, the mathematical study of what is popularly known as chaos theory, are becoming ever more critical to approaching the most challenging problems. "Dynamical systems are so complicated that a computer can help us to understand, but we have to understand how to use it effectively," Galatolo said.

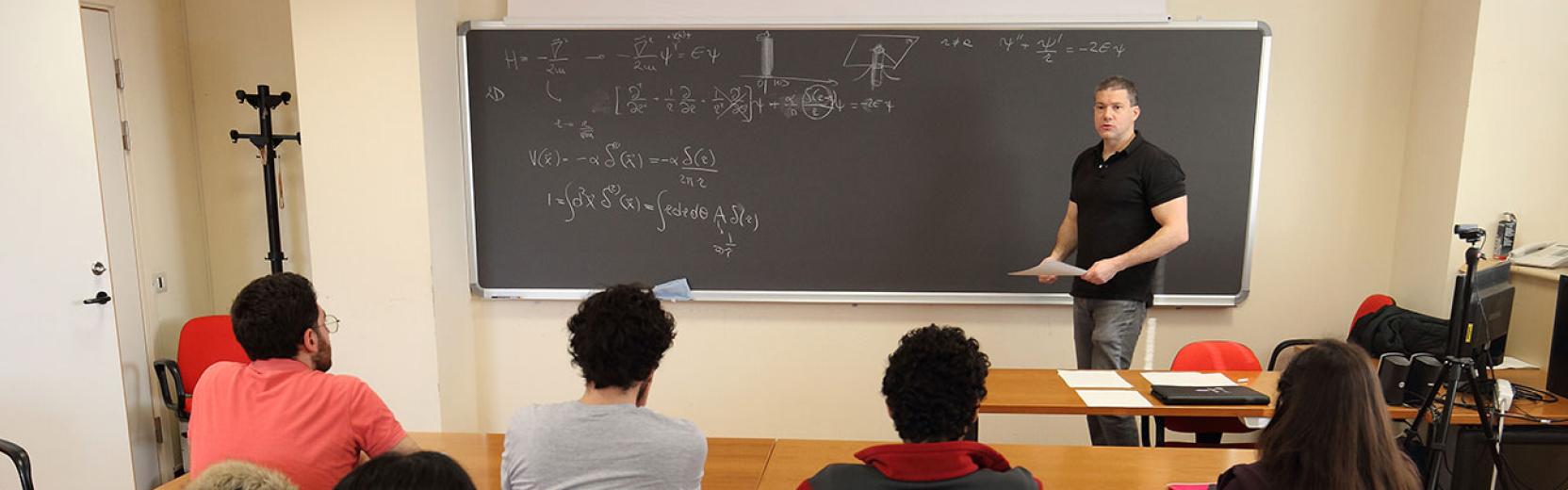

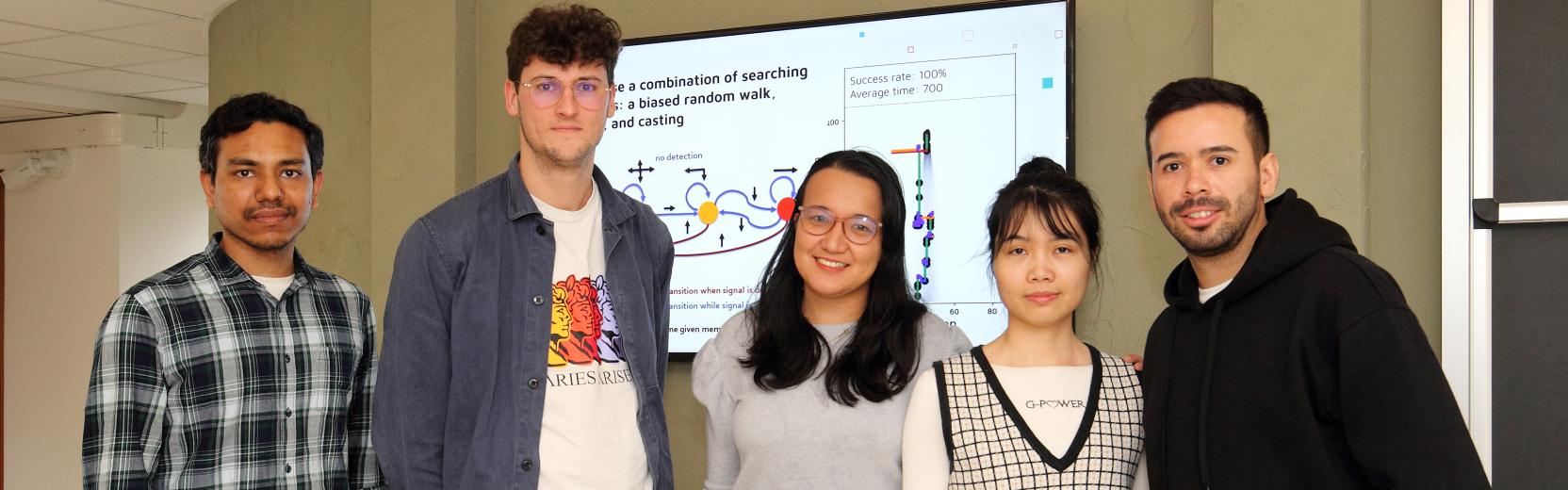

A main purpose of the school at ICTP was to share the field's current computational techniques with young researchers, bringing together experts and students to discuss the students' problems. While the largest contingent of attendees were young professors, Galatolo estimated that about one-quarter of the participants were students. "People met and discussed the work of the young people, helping them to understand and finding the right direction. That for me was one of the main goals," Galatolo said.

Rafael Lucena, a PhD student co-tutored at the Federal University of Rio de Janiero (UFRJ) and the University of Pisa, had the opportunity to speak with an expert on his area of research who gave him many ideas to solve the final subproblem of his thesis. "I don't know yet whether it will work, but for sure it was very helpful," Lucena said.

The first week of the school focused on the question of computation -- how to use computerized tools to advance the field. "Mathematical objects lie in the platonic world of ideas. We want to find a way to compute these objects in a mathematically rigorous way, to keep track of the errors," explained Isaia Nisoli, a professor at UFRJ and a lecturer at the school. "Doing a rigorous computation is finding an object that you can touch with a computer that lies near an object in the world of ideas - the abstract mathematical object."

"Such computation is very important because it tells you a lot about the statistical properties of the underlying system," said Wael Bahsoun of Loughborough University in the UK, a lecturer at the school who studies dynamical systems from a probabilistic point of view, a branch known as ergodic theory.

With computational techniques under their belts, the school's participants turned to a different question in the second week: what are the limits of computation, and are there problems that can't be solved with a computer? Especially for researchers like Lucena and UFRJ professor Maurizio Monge, a lecturer at the school, who are more familiar with the question of computation, the issue of computability is intriguing. "For me, it's a new topic so I have very much to learn," Monge said.

The conference was funded under the auspices of BREUDS, the Brazil - European Union partnership in Dynamical Systems. This research program allows for the exchange of scientists between Europe and Brazil, which is now one of the world leaders in the field. "This is not only a way to help them but also conversely they help us because in this field they are really strong,"Galatolo said. Monge agreed: "The environment is very motivated, and there are a lot of possibilities."

Due to the international nature of the conference, ICTP was the perfect venue to host mathematicians from Europe, Brazil, and beyond. Nisoli was excited to be at ICTP, a place he called "one of the engines that put in movement the world of science."

For many participants, the highlight of the workshop was its small size and interactive nature. "I really enjoyed the school and liked the idea of the organization, very informal, that people ask as many questions as they want and have plenty of time to discuss and collaborate," Bahsoun said.

"Certainly, it was very good for spending some time with people working in my field, and the informal context is even better than the workshop where someone is just lecturing," Monge added.

The school's small size didn't mean small ideas, however. The structured time for discussion and brainstorming led not only to new solutions, but ever more questions. Bahsoun said he left the conference with four or five ideas for collaboration with other researchers. "It's very productive - not only in the sense of just producing new problems to work on but I really learned also a lot from other people, what they are doing and what the techniques available are."

Nisoli said that the researchers at the conference are spoiled for choice when it comes to future research questions. He likened the experience of the school to being in a garden full of fruit and having such trouble deciding what to pick that one ends up starving. "We have now a lot of interesting 'homework,' " Galatolo agreed. "Maybe too much!"