In collaboration with the Institut Català de Paleontologia (ICP)

Miquel Crusafont in Spain, ICTP's Multidisciplinary Laboratory is

examining the insides of 70-million-year-old dinosaur teeth without

even grazing the surface. The teeth are just one piece of a larger

body of work to ultimately determine how diverse the dinosaur

population was shortly before a catastrophic event wiped it from

the face of the Earth.

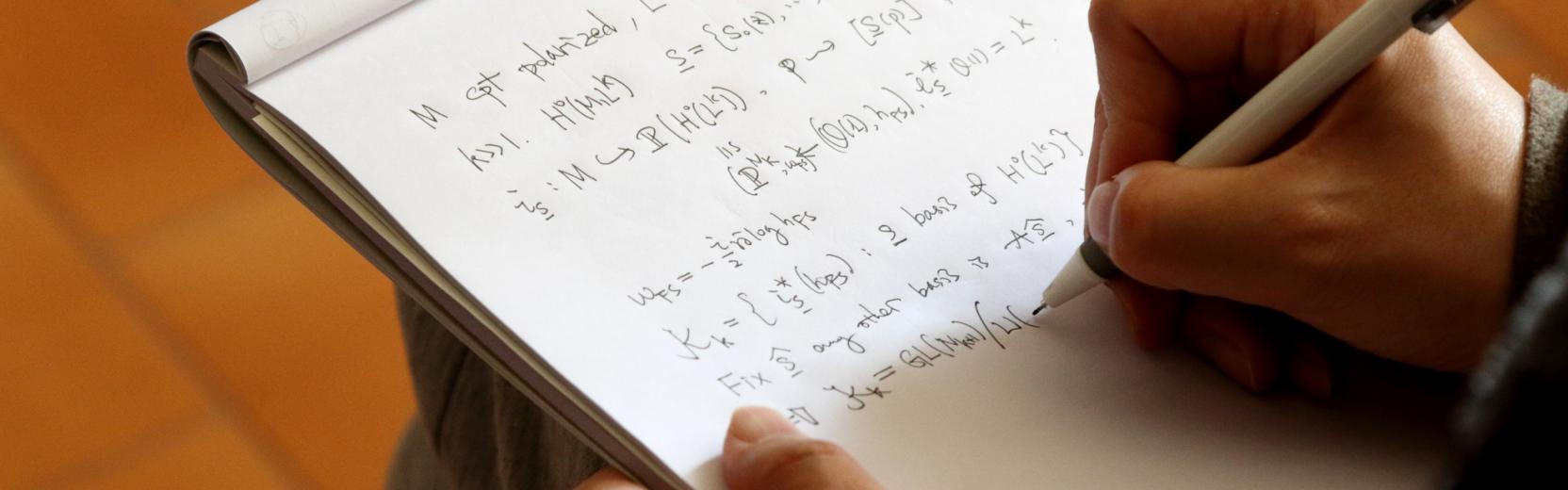

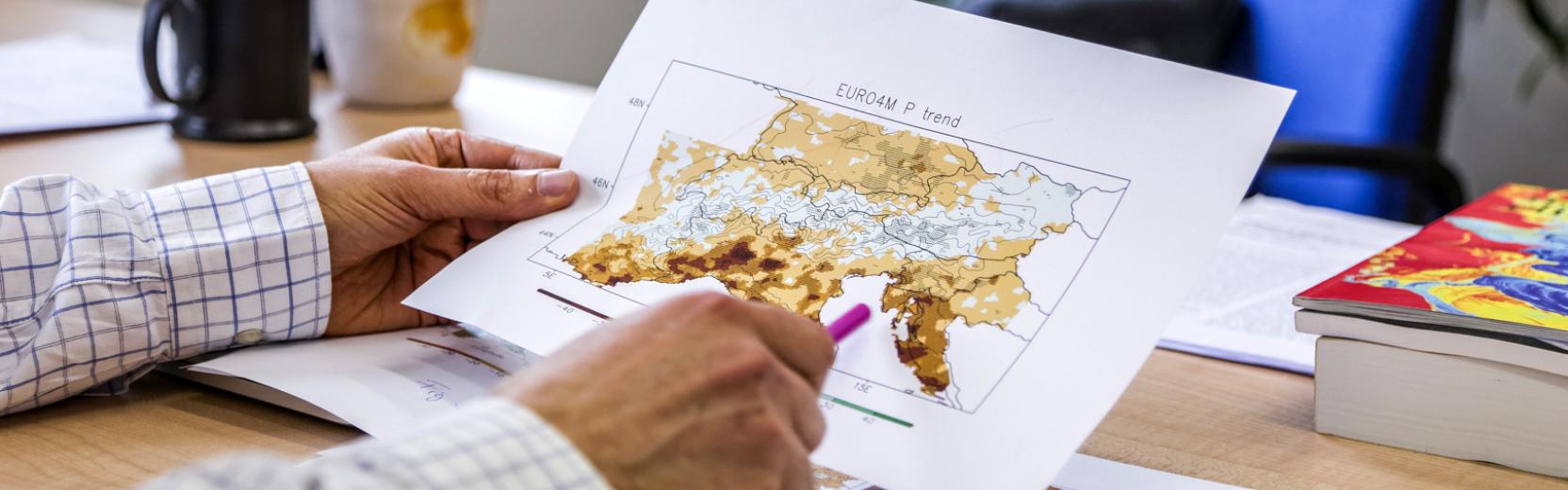

Using the Mlab advanced X-ray microCT system, ICTP scientists

Federico Bernardini and Clément Zanolli scan the teeth and

construct, using special algoritms, 3D images of both their outside

and inside morphologies. This way, scientists can gather

information about the structure of the teeth, thickness of their

enamel and what kind of food the dinosaurs ate while preserving the

tooth in its natural, rock-encrusted form.

"Such tiny teeth are sometimes too fragile to extract from the

rock and the accurate 3D reconstruction obtained by the micro

computed tomography allows for their systematic study and

classification," says ICTP scientist Claudio Tuniz, who coordinates

the Centre's X-ray imaging laboratory.

The leader of the research, Angel Galobart of ICP, has been

studying and classifying dinosaur teeth, bones and tracks for

nearly thirty years. He uses the distinguishing characteristics in

teeth from dinosaurs of different species to establish

classification systems, which he then uses to determine how diverse

the dinosaur population was during the last 5 million years of its

existence.

His current focus is in the southern part of the Pyrenees in

Spain, where he and his colleagues have discovered a wide diversity

within the last of the sauropods--the largest of the dinosaurs

known for their long tales and necks--and ornithopods, a type of

herbivore dinosaur. But the teeth he brought to ICTP this week are

of a different sort: a group of carnivorous dinosaurs called

theropods from which some of the birds of today evolved. In a way,

theropod diversity is the last piece of the Pyrenees puzzle.

"It's incredibly important that we determine how diverse theropods

were in this region," Galobart says. "We want to know about the

health of the dinosaur population during this time span [between 70

and 66 million years ago]. If we get a great diversity of theropod

dinosaurs, as we have seen with the other members of sauropods and

ornithopods, this will mean that the ecological conditions were

good enough for dinosaurs to continue living on Earth if the

asteroid impact had not occurred."

"This kind of research allows us to see the entire terrestrial

heritage in context and thus adds value to our own cultural

heritage," Tuniz says.

The x-ray microCT laboratory was developed in collaboration

with Sincrotrone Trieste as parte of the ICTP/Elettra

EXACT Project funded by Regione Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy.