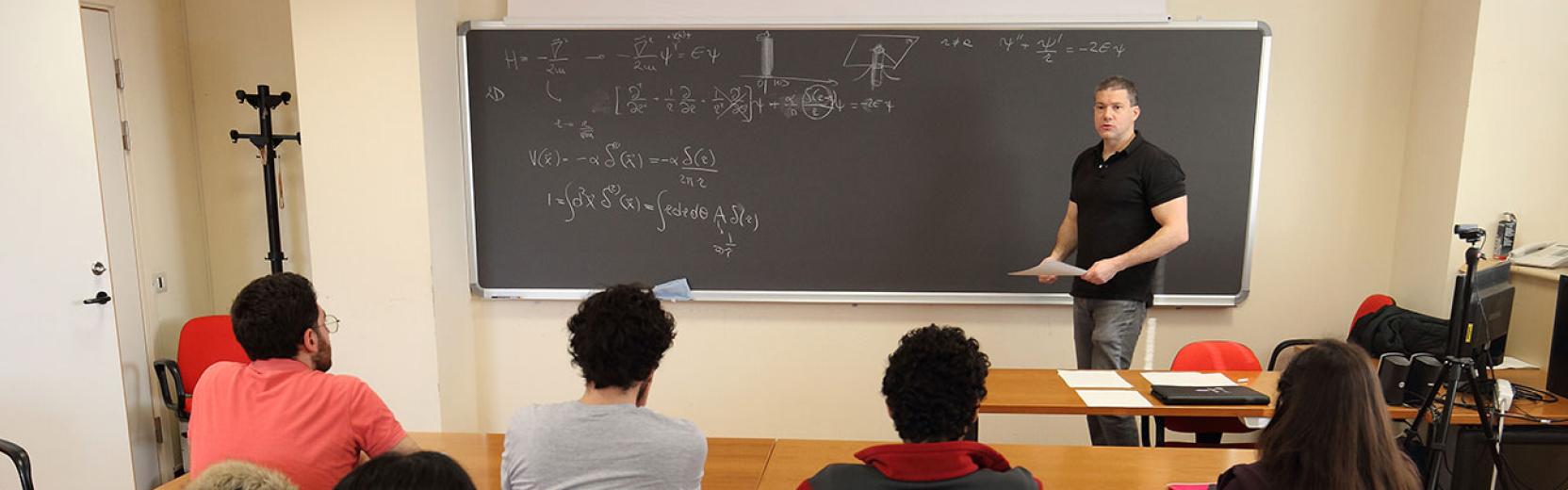

Every year, the Ramanujan Prize ceremony becomes an occasion for ICTP to celebrate mathematics. On 9 December 2025, ICTP and the International Mathematical Union celebrated the work of this year’s award winner, mathematician Claudio Muñoz of the University of Chile, who received the prize from ICTP Director Atish Dabholkar and IMU Secretary General Christoph Sorger.

At the event, Muñoz gave a talk presenting his work on dispersive partial differential equations, focussing on a specific class of solutions of the Standard Model in one spatial dimension. In this interview, he speaks about how his interest in mathematics developed, his struggle to choose between maths and astronomy, and his experience as a mathematician working on physical problems.

What inspired you to study mathematics?

I had a high-school professor who played a very important role in my life. His name was Archimedes, so there was a mathematical spirit already in his name. He used to go the extra mile with us, with him we used to do more than usually expected in a math curriculum at that level, and we used to work in a very collaborative way. The agreement between him and us was that learning was compensated with more learning: the more effort we put into solving problems, the more mathematics he would teach us. We enjoyed learning that way! That laid a very good foundation, without which I would not have been able to go this far in mathematics.

How did you then decide to do mathematics at university?

The system at the University of Chile is particular. I attended an engineering school, where at the beginning, you only study the basics in all scientific disciplines. Only after the first two and a half years do the students get to choose among various options. It took me a while to decide to go for mathematics, because I have always had a big passion for astronomy. I chose mathematics, however, because at that time astronomy involved a lot of data reduction and astronomers were spending a lot of time in front of a computer, without the sophisticated techniques that exist today to analyse data. I preferred to work with pen and paper. Now I can see many connections between what I do and astronomy and I am trying to move in that direction with the tools that I have.

Could you summarise in a few, simple words the essence of your work?

As I always say, I love to work on everything that is wave-like. I’m interested in understanding how waves behave, and waves are everywhere. They might seem to pertain to very different domains: quantum physics, gravitation or fluid dynamics, but these are all different manifestations of the same phenomenon, and that is what I work on.

You are very interested in problems that have a connection with physics. How is your point of view different from that of a physicist and what does your approach bring to the table?

For me physics is a source of inspiration, an infinite source of questions. I find physical problems beautiful and profound. Some of them have a mathematical formulation that allows one to do maths. The difference from physics lies in the questions we ask. We mathematicians believe that one should always try to solve the most fundamental problems first. Think of General Relativity. Physicists have been working with that theory for more than a century. They have been publishing papers about black holes and there is a huge literature about that. Mathematicians, instead, have only just been able to rigorously prove that a rotating black hole is stable, and the proof is about a thousand pages long. Think about that. It’s a huge, monumental work, but it is fundamental for mathematicians. The authors, Elena Giorgi, Sergiu Klainerman and Jérémie Szeftel, started several years before by proving mathematically something even more fundamental: that the Minkowski space is stable, as proved by Christoudoulu and Klainerman. That’s how we proceed.

Your talk at the ceremony focused on results for the Standard Model in 1+1 dimensions, while physicists have been focusing on it in 3+1 dimensions, because it corresponds to the world we live in. Can you help us understand why it is so important for a mathematician to solve the Standard Model in a one-dimensional space?

You always have to think of mathematics as a ladder. I have focused on the 1+1-dimensional case because I do not know how to solve more complex problems. But I know that solving math problems is like climbing a ladder. You cannot immediately solve the most complex version of a problem; you need to simplify it first. Other mathematicians have tackled the problem in 3+1 dimensions in the past, but considering only one part of the model. Then we realized that it was possible to solve it in its entirety by considering a lower dimensional space. Once we understand the 1+1-dimensional case, we will go up the ladder and move to a higher dimensional space. It will take time, though. Within ten years I would like to have made some progress on understanding the Standard Model in 3+1 dimensions, even if by then physicists might be able to tell us that the Standard Model is obsolete.

More and more people seem to appreciate the importance of mathematics also thanks to its applications, AI to begin with.

Yes. At the University of Chile, we have a track in mathematical engineering. Every year, half of the students who graduate move to industry, and they are in very high demand. That’s because while many people nowadays know something about AI and data analysis, very few really understand them. But that is an essential piece of knowledge if one wants to innovate. Mathematicians have the tools to understand things deeply, which is a strength, but also a drawback, because that takes a lot of time.

What has the Ramanujan Prize meant to you?

It has been a huge honour. Many people have reached out to me and have congratulated me since the prize was announced last October. I have felt the love and the support of many people who have expressed their respect. It has not only been a scientific honour; it is also people’s appreciation for what I have done that has meant a lot to me.

After the ceremony, you met the ICTP Diploma students in mathematics. How has it been to talk with them?

I was really impressed by the fact that they come from very far away: Latin America, Africa and Asia. They had read my biography and I was struck by the very concrete questions they asked. They wanted to know why I left the US and then left France to go back to Chile. It was difficult to explain that one might want to go back to a developing country like mine and that my decisions were not only based on science. Students are very motivated by science: they want to get better at what they do, learn more and become successful scientists. They also want better living conditions and for some of them it is simply complicated, even dangerous, to go back. It was not that difficult for me. In Chile, it is possible to do science and I went back because I wanted to be closer to my family. I realise that’s an uncommon choice, people usually do that at the end of their career, once they are accomplished. These life decisions can be harder than mathematical problems sometimes.

This was your first time at ICTP. What were your impressions?

Even though I did not know much about ICTP before, I am very impressed by the work that ICTP does and I am glad that such an institute exists. During my time here, I had discussions with the ICTP Director and with several members of the Mathematics section. I hope this will be a starting point for a future collaboration, not only with me, but also with my country, Chile.

Pictures of the 2025 Ramanujan Prize Ceremony can be found on ICTP’s Flickr album.