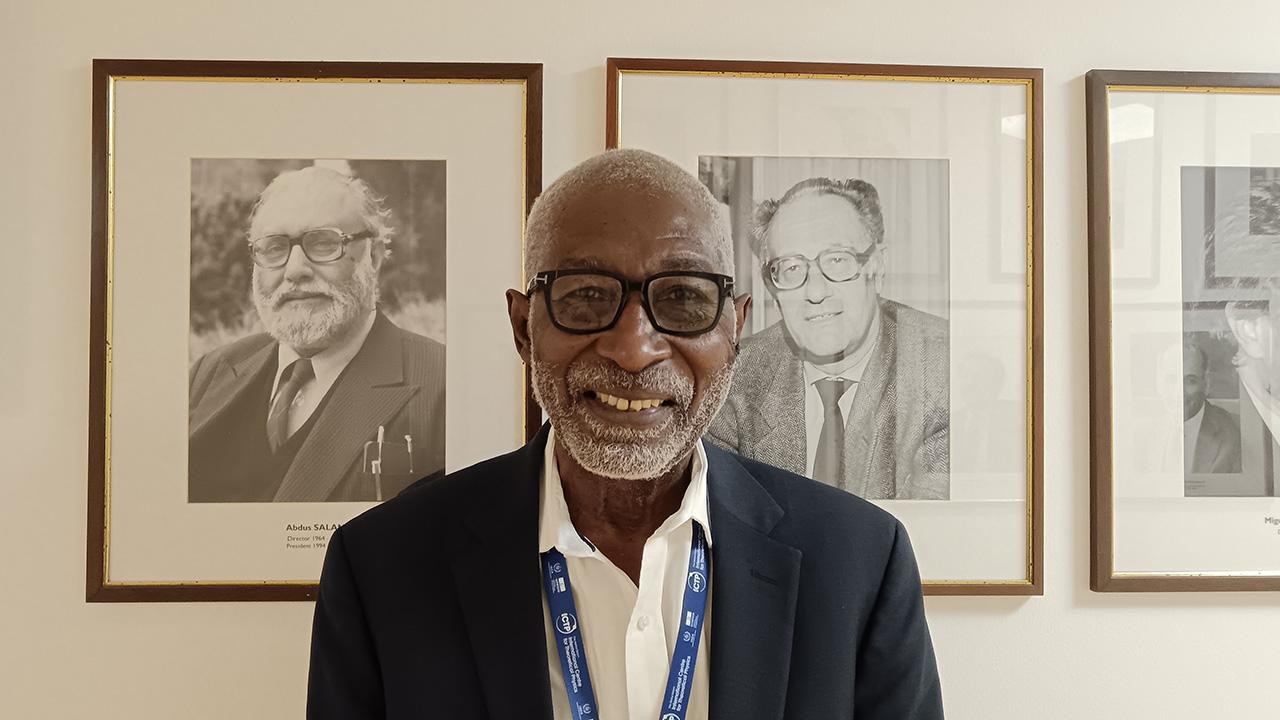

Nii Quaynor is a scientist and engineer from Ghana, known for the major role he has played in connecting Africa to the internet.

Having grown up in Ghana, Quaynor moved to the United States to study engineering and computer science. He completed undergraduate degrees at Dartmouth College, and then earned an MSc and a PhD in computer science from the State University of New York at Stony Brook. In 1994, he established the first internet service provider in Ghana, and went on to assist in implementing it across sub-Saharan Africa. Among the numerous awards that have recognized his contributions, in 2013 he was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame by the Internet Society.

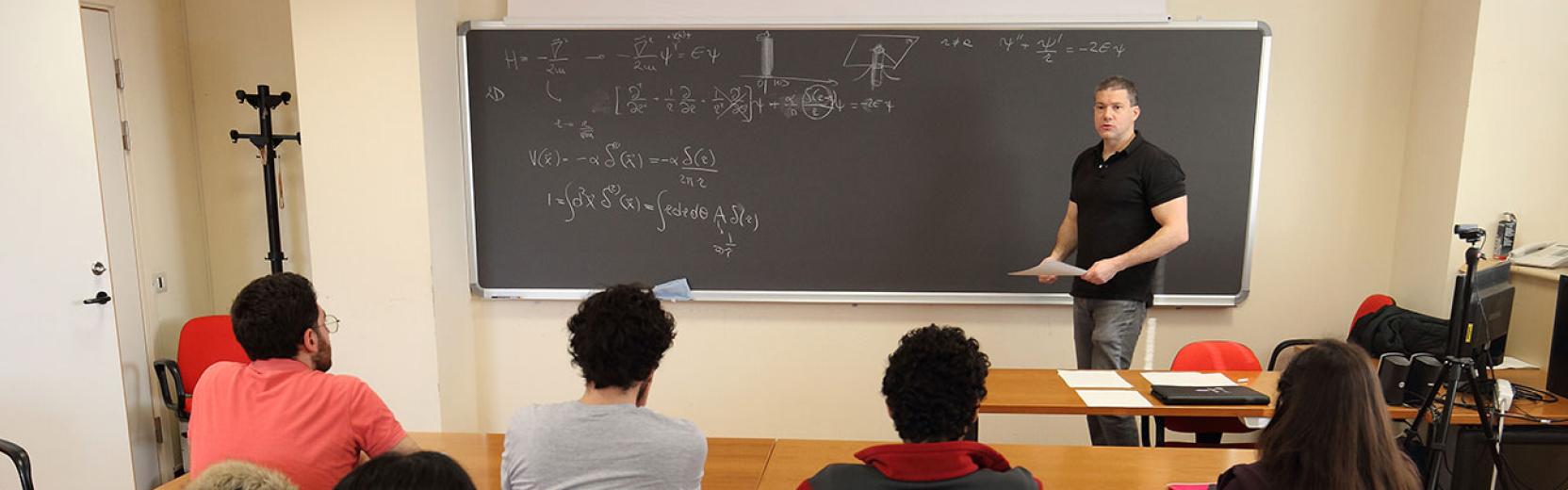

Quaynor visited ICTP last September as a keynote speaker at the Workshop on Empowering Connectivity: Bridging Space and Earth with DTN organised by ICTP’s Science, Technology and Innovation unit. DTN, or Delay Tolerant Networking, is a network architecture designed to ensure reliable communication and information transmission in environments with unreliable connectivity, such as Space or remote areas on Earth. It does that by using data storage and forwarding techniques.

In his talk, Quaynor traced the evolution of connectivity in Ghana, from the early days of the Internet to today’s challenges. We met him on this occasion to learn more about his experience and vision.

To give some context, can you tell us what your interest is in this conference and why it is important?

There are many places both on Earth and far into space, where for one reason or another we have to accept that the links in the internet are less reliable, meaning that when one is ready to transfer the information, the connection is not there. The internet as we know it now does not allow you to transfer data when that is the case, and it thus favours those who are able to receive the information in real time. DTN is about finding a way to accommodate the delays and disruptions in the connection, which are inherent in space communication, and which also affect what is probably the majority of the population, including people who live in isolated and remote regions of my country, Ghana, and Africa at large. My interest in that sense is to make sure that the two networks, DTN and the internet, are somehow coupled, so that we can benefit both from real-time communication and from DTN.

You studied in some of the best universities of the United States and worked there, both as a researcher and in the private sector. What motivated you to go back to Ghana?

I tried to go back twice. The first time I only stayed for three years, during which I founded the department of computer science at the University of Cape Coast. That was my first attempt at introducing computer science into the Ghanaian educational system. But after realising the effort it takes to move anything in the country, I decided to go back to the US, to work in the private sector. The second time I moved back to Ghana was in 1988, and I went there as a UN consultant. It was to help the national oil corporation build capacity in processing data during the exploration phase. I ended up building a company that supports technical computing.

How did that happen?

Building capacity in exploration data processing in Ghana required bringing some specific digital equipment from the US. Once I did that, I realised that I had to find a way to support that equipment and make it sustainable. I had to make sure that there were engineers with the right skillset to repair it, and computer scientists familiar with the software to sustain the installation, which otherwise would have collapsed in a very short time. So, I built a private company that did exactly that.

How did you then become the father of the internet in Africa?

The technology that I had brought to Ghana for data processing was the same that at that time, in the early 1990s, was used for internet connectivity. I was familiar with it and, as the internet was becoming more and more important, I realised that we needed to improve communications in Ghana. Knowing the machines and being a senior engineer manager at the US company that provided this technology, I had an advantage, so I started teaching people what I knew. And that’s essentially what I have been doing all the time. I did not know that one day someone would have called me the father of the internet. I am mostly a teacher. Most of my job has been hands-on teaching, and that is also what I did at ICTP.

Tell us about it.

When I was at the University of Cape Coast to start the computer science department, I was surrounded by many physicists, because there were no computer scientists in Ghana at the time. From them, I learnt about ICTP and the workshops that were organized in Trieste at the time, particularly on microprocessors. I came here first as a student, probably in 1982, and then, when I returned to the US for a short period of time, I became a lecturer and came to Trieste to teach, probably in 1987, before beginning work with the UN.

What is the state of the internet in Africa now and what are the priorities there?

I think Africa has not succeeded in owning the internet. It has given up. In a way, it is as if we had said “I cannot do it, do it for me,” which I think needs to be fixed.

How?

It is very difficult, almost like the digital divide, because the internet is now owned by large multinationals, which manage to provide us with the infrastructure at a very low cost, while making us more and more dependent on them. We must find something unique that we can do to add value to the internet. And part of the problem is that we are not able to find what our unique added value is. To a lesser extent this is also true for Europe, but Europe is much ahead, while we have completely given up. For that we need help. We need to reinforce South-South cooperation, and to collaborate with centres like ICTP, which want to work with the Global South. That is very important for our independence.

ICTP has recently launched the International Consortium for Scientific Computing (ICOMP), which aims to bridge the knowledge and technological gap in high performance computing, Artificial Intelligence and quantum computing. What is your advice on what ICOMP’s priorities should be in Africa?

I think that the project that you are describing can greatly benefit research and education in Africa. I am a board member of both the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences and the Ghanaian Academic and Research Network and I think that ICTP can do a lot to train African researchers in high performance computing, Artificial Intelligence and quantum computing by collaborating with these networks.

Do you still believe that training is the main priority?

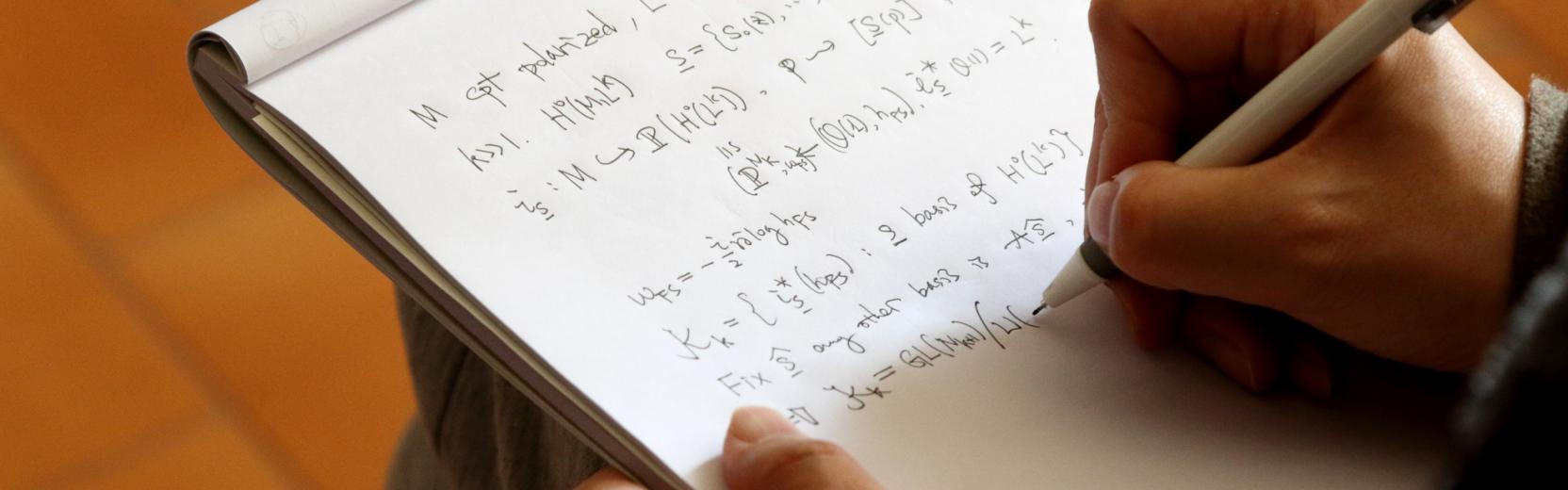

I have no doubt about it. All scientific training results in some form of impact, be it in policy making, engineering, development. And I believe that training is still the most important thing that ICTP can do. ICTP should keep organizing events in the Global South and invite scientists from the Global South to attend your workshops in Trieste and encourage them to express themselves and to find new problems and bring solutions. What is most important is to stir the ecosystem and stimulate knowledge locally. By knowledge I do not mean mere notions. Knowledge is about being able to think by oneself, to solve problems, to find new solutions. Knowledge is built by discussing with other people and by making mistakes and finding new ways to solve problems. This is what countries need the most.

You seem to believe that ICTP’s mission is still relevant.

Very much so. There are not many research centres in the world that collaborate with researchers from the Global South, and if you stop, we are in trouble.