Work-life balance, cultural norms, discrimination, wages, stability; all well-known challenges to female professional development. Female scientists still find the path to a research career filled with roadblocks, with particular problems affecting women from emerging economies. According to the UN, female scientists are often underrepresented in high-profile journals, passed over for promotions, and given smaller research grants than male collegues. Their careers are also generally shorter and less well-paid than those of men.

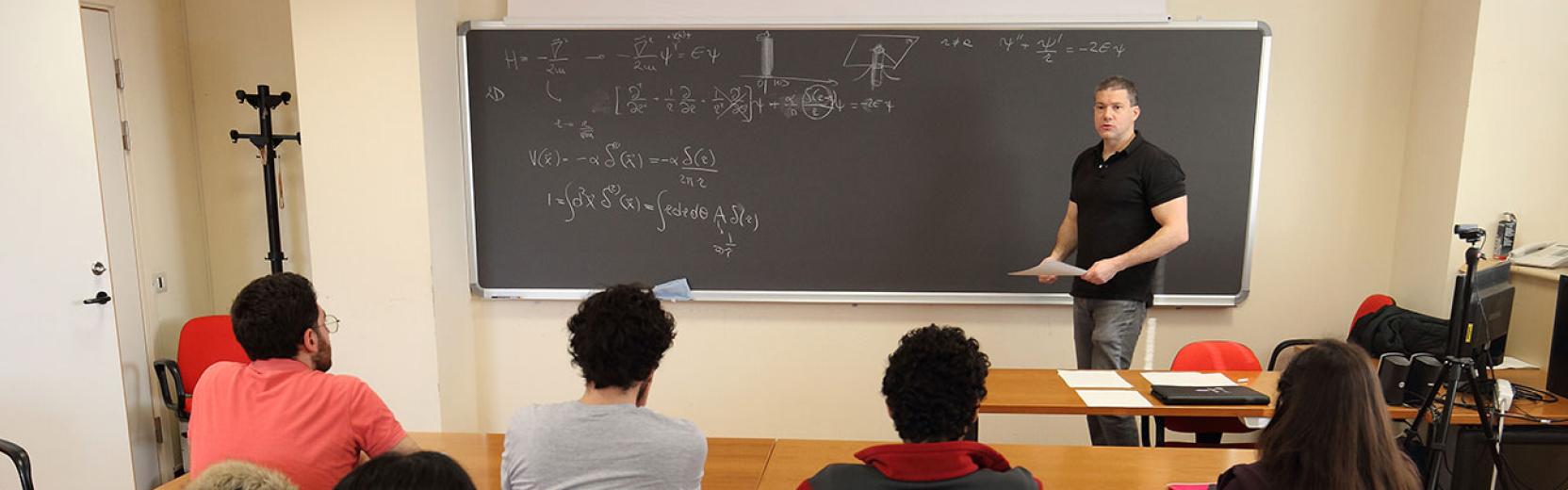

Physics Without Frontiers (PWF) was founded over ten years ago by HECAP and Atlas members Kate Shaw and Bobby Acharya, with the idea of bridging the gap between the opportunities available to scientists in the Global North and those in science and technology-lagging countries. As ICTP celebrates the International Day of Women and Girls in Science 2024, Kate Shaw talks about PWF, and ways to address the bias in global science.

Could you summarize what you do with PWF?

Physics Without Frontiers, or PWF, is about access to science, which you can also talk about as diversity in science. Science, like many other human procedures, should be accessible to everybody, no matter your gender, region, birth, or economic status. Everybody should have access to scientific information; be able to become scientifically literate, go on to study, and have the possibility of a career in science. And, as is common in many aspects of the modern world, this is very dependent on who you are; on your gender, which country you were born in, your economic status and ethnicity. Many things affect your right to access science.

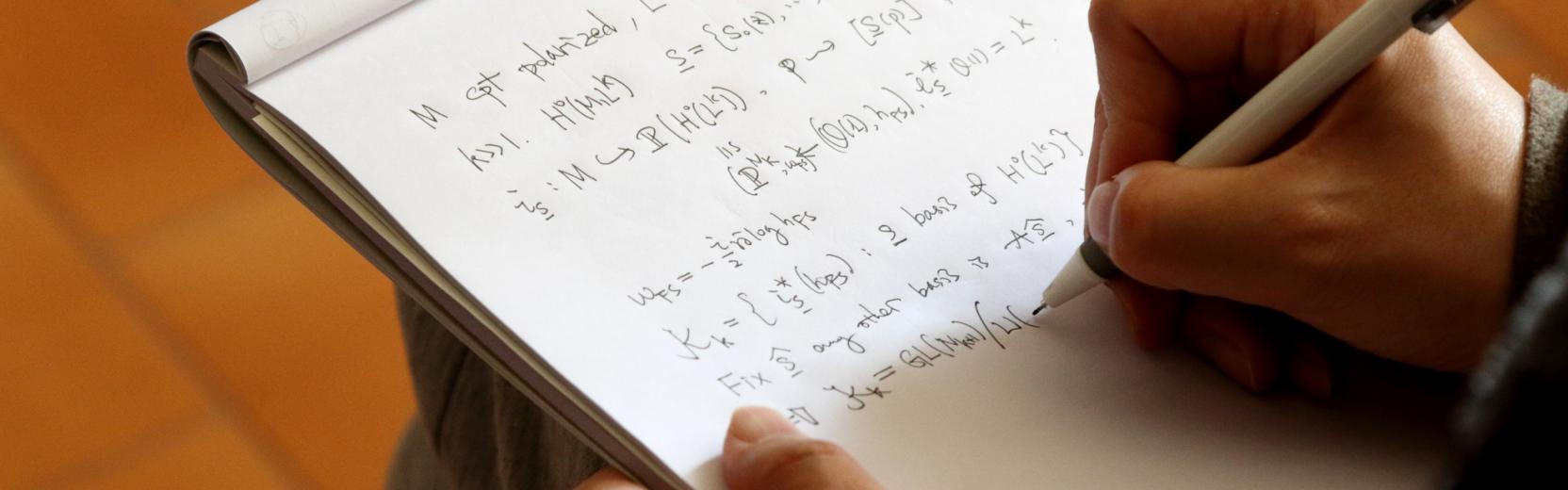

Ensuring that science is really accessible to everybody is important for sustainable development and scientific literacy. PWF is about breaking down barriers in an international context by looking at all the different frontiers of science. We work a lot with least-developed countries; with students and young people in areas with very little access to science. We also work with our volunteer network, many of whom are alumni of our activities. Many of these people are from least-developed countries or minorities, and have a passion to make sure everyone has access to science. We run all sorts of activities to support mostly university students, although we also work with younger people and master's students, helping them get access to opportunities, to run training activities for schools, and do communication projects.

What is the gender distribution of students involved in your programs?

Each program we run is really different. If we're working in the Middle East, 70 to 90 % of our students are female, whereas in Nepal, 1 to 5 % will be female. The issue of gender is very societal; it completely depends on which society and region within a country you're working in. In general, women are underrepresented in physics, although there are various countries in the Middle East where we have plenty of women at the undergraduate level.

“In many Western countries, it's thought that hard sciences are masculine topics; that's what we're told through many different types of media and social ideas.”

The gender gap comes from society. In certain countries, it depends on whether young women are encouraged to go into undergraduate physics or STEM subjects. In many Western countries, it's thought that hard sciences are masculine topics; that's what we're told through many different types of media and social ideas.

In the Middle Eastern countries we work in, these topics are not genderised. The young people feel they can do anything when they go to university, and they’re not pushed into one topic or another.

However, jobs are often genderized. It could be difficult for a woman to become a taxi driver, as that's a typically male job. Teachers are generally, though not only, female. In conservative environments, a very acceptable job for a woman to have is teaching. In that way, they can fill other classically feminine roles in the household. They can study whatever they like at university, it could be history, physics, art, because they will go on to be a teacher. This just shows you that when you take away this idea of genderising academia, women will choose physics, just as anyone will choose any other field. It's not intrinsically a male subject.

Taking the example of Nepal, why do you think it's so different there?

So, I worked in Palestine a lot in the Middle East, and one of the wonderful things about working in Palestine is the very high level of literacy there. Having a high level of literacy means that many people are going to university. Something like 30 % of people go to university in Palestine, which is very high for the region. That’s great, as we don't have to convince people to go to university. Also, 50 % of people who go to university are women.

“There are a number of issues to address: one is young women feeling that science, especially physics, isn’t a career that they can go into.”

In Nepal, there is an issue with literacy. They don’t have a 50–50 balance of females and males going to university, and there are issues related to girls going to high school. This is seen more in rural areas than in the cities. So, when you're looking at addressing the issue of gender in physics, it’s actually a huge undertaking. Suddenly, you have to look at why women aren't going to high school. Why educating women isn't intrinsically part of the society there. Again, it's to do with society and gender roles.

What are the major roadblocks to getting women into science?

There are a number of issues to address: one is young women feeling that science, especially physics, isn’t a career that they can go into. That's a big roadblock. It starts with toys, from a young age: engineering and Lego for boys and dollies and make up for girls. This is a huge issue everywhere you go, and nothing that we can really do addresses it. For us to address the societal issues, it would be more about doing more advertising of science in general, advertising physics, and sharing fantastic role models.

“We all naturally encourage the status quo unless we make an active effort to go against it.”

In South Africa, we did a poster campaign showcasing South African women in physics. These sorts of projects can be really impactful, especially for young people, because imagery can change your ideas as to what you're able to do. We definitely want to do more on role models and positive imagery.

How do you think bias affects PWF projects?

There are various aspects we consider, when it comes to bias. We all naturally encourage the status quo unless we make an active effort to go against it. So, when people apply for PWF schools and activities, we ask our volunteers to be aware of diversity, to track gender and try to include as many females as possible.

When you're talking to a class of, say, 100 students, the male students can often be very confident, and we ask them questions. In many countries, women are brought up to not speak up; to be quiet, and a good citizen. This is just ingrained, and it’s a strong effect. For this reason, it can be more difficult to communicate with the female students, not because they don’t have the same capability, but because it's been ingrained in them that this is how they should communicate in a large class.

How does PWF help underrepresented scientists?

We've had many, many females go on to further studies through our mentoring program, giving them the opportunity, through our networks, to go on to Masters and PhD studies, and we've got wonderful stories of them being able to continue in science. Many of them had children and still managed to working with their families. However, I think we've still had a very small impact.

When running our programs, we make sure we’re being very gender-aware. We educate and train people about awareness when considering applications to schools, workshops and activities. In some countries, people from ethnic minorities experience the same kind of exclusion, so we make sure diversity is at the heart of the discussion, and not just in terms of gender.

LINKS:

UN International Day of Women and Girls in Science