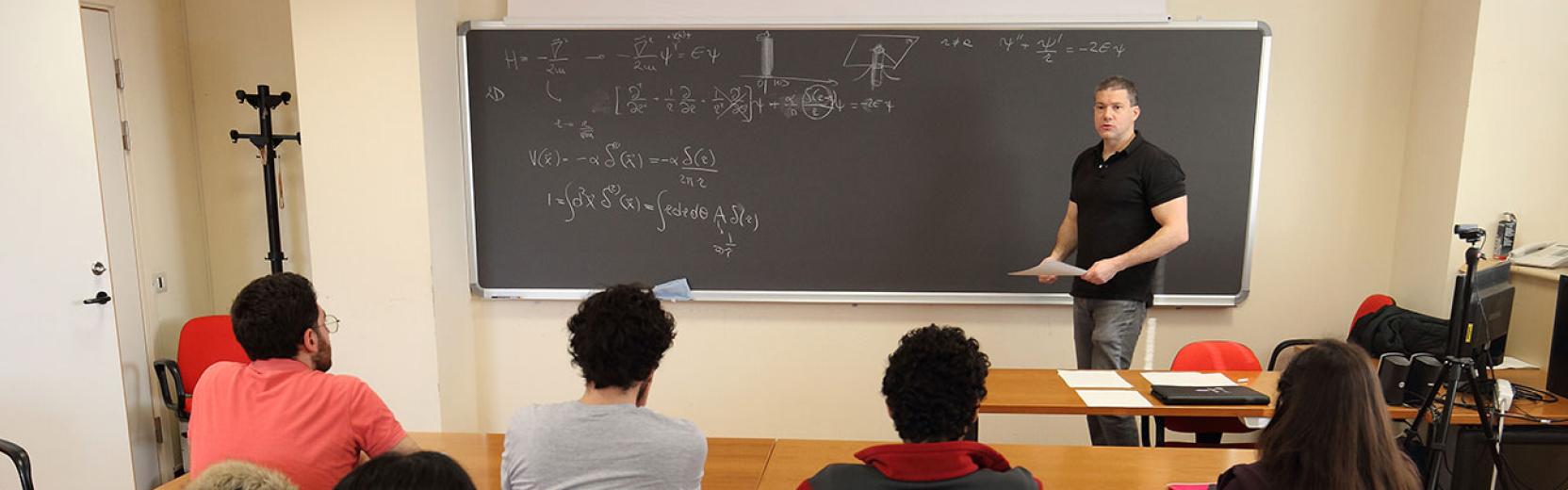

“We need a science diplomacy for sustainable development goals.” These words, spoken at the opening of the 2016 American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)-The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) Course on Science Diplomacy by TWAS Interim Executive Director Mohamed H.A. Hassan, set the tone for a week-long event devoted to the growing role of science and technology in international relations.

ICTP has long been involved in science diplomacy throughout its history; ICTP Director Fernando Quevedo highlighted several key examples in his speech during the course’s opening ceremony. “Science is the same in every part of the world and doesn’t see any difference in nationality, belief or tradition. For instance, UNESCO and ICTP are very much active in an institution call SESAME, one of the biggest synchrotron facilities in the Middle East, in Jordan. The work done there has many applications, from physical science to biology, and it is an example of concrete science diplomacy, with different people from Iran to Israel working together in research activities,” he said.

At the time of ICTP's founding by Nobel Prize Laureate Abdus Salam in 1964—in the middle of the Cold War—scientists both from Eastern and Western blocks came to ICTP to work together. “This was a real example of what science diplomacy is,” reflects Quevedo. Scientific institutions can make quite a difference, he adds: “CERN, for instance, is a great example of how communities, from different countries and traditions, can join together to make great discoveries. Here at ICTP, with people from 180 countries all over the word, we are trying to create a culture of science in every country, to sow the creation of better experimental facilities, and to further the development of science diplomacy.”

Rush Holt, CEO of the AAAS and a former U.S. Representative, also spoke at the opening ceremony about the role of science and scientists in diplomatic relations. “We have to consider the indirect, but real, benefits due to this approach: scientists regularly operate without attention to national boundaries, and often break down roadblocks that politicians or diplomats can see as impenetrable,” says Holt. “This course, and others like this, are becoming even more recognized as essential to overall diplomatic goals. If you think about the Zika or Ebola crises, they highlight the need for cooperation in medical research and, in general, the requirement to apply science diplomacy in a systematic way.”

Other prominent speakers at the course, which ran from 11 to 15 July, included Princess Sumaya bint El Hassan, the president of the Royal Scientific Society of Jordan, and Vaughan Turekian, science and technology adviser to the U.S. Secretary of State.

--Alessandro Vitale