When Thomas Kibble, Phillip James Peebles, and Martin John Rees began their research careers in theoretical physics in the 1950s and 60s, many facets of cosmology and fundamental physics were still unexplored. It was the groundbreaking work done by these three theoretical physicists, now considered "giants" in the field, that opened up many aspects of cosmology, astrophysics and fundamental physics for future research. For this, they were awarded the 2013 Dirac Medal, and the three came together at ICTP for the Dirac Medal ceremony on 8 August 2014.

The journey in physics began with degrees in mathematics for Kibble and Rees, and one in engineering for Peebles. "I started out doing mathematics," says Kibble, "but having done an undergraduate degree and looking around at what was available, it seemed to me at that time that the most interesting things were in theoretical physics. So, I went in that direction."

For Rees, it was a combination of finding a charismatic advisor in British physicist Dennis Sciama, one of the fathers of modern cosmology, and "exciting times" that led to a career in physics. "This was in the mid-1960s, when the first evidence of blackholes and the big bang was emerging. It was good to be a young person in the subject," he says.

Peebles too was inspired by his advisor, American physicist Robert Dicke, when he went to Princeton University to pursue a PhD in particle physics. "Dicke was one of the people to recognize that gravity physics was not being at all explored on the experimental side. The work he was doing was so fascinating that I followed in his footsteps," he says. Credited by many for establishing cosmology as a quantitative branch of physics, Peebles chose to do cosmology because he felt it was being neglected. "[The time] was ripe for a young person to start doing meaningful studies," he says.

Today, with fresh observational and experimental data flowing in, Rees and Peebles say it will be interesting times for cosmology, and they broadly classify two sets of challenges for cosmologists. One is to use the data and understand how from a simple beginning our complex cosmos with the galaxies, stars and planets emerged; the other is to understand the fundamental nature of our universe with its atoms, dark matter, and radiation, and whether it is part of a grander multiverse.

As for particle physics, Kibble says it has reached a "peculiar situation". On one hand, researchers have collected a tremendous amount of new experimental data, which he says "has provided extraordinarily precise and comprehensive understanding of the field." On the other hand, there are big questions about the nature of dark matter and dark energy and how gravity can fit in with other forces that remain unanswered. "I think theoretical speculation is well and good, but it has to be ultimately tied to observation if it is going to mean anything," he says. But both Rees and Kibble say that answers to these fundamental questions could lie in cosmological observations rather than direct experiments.

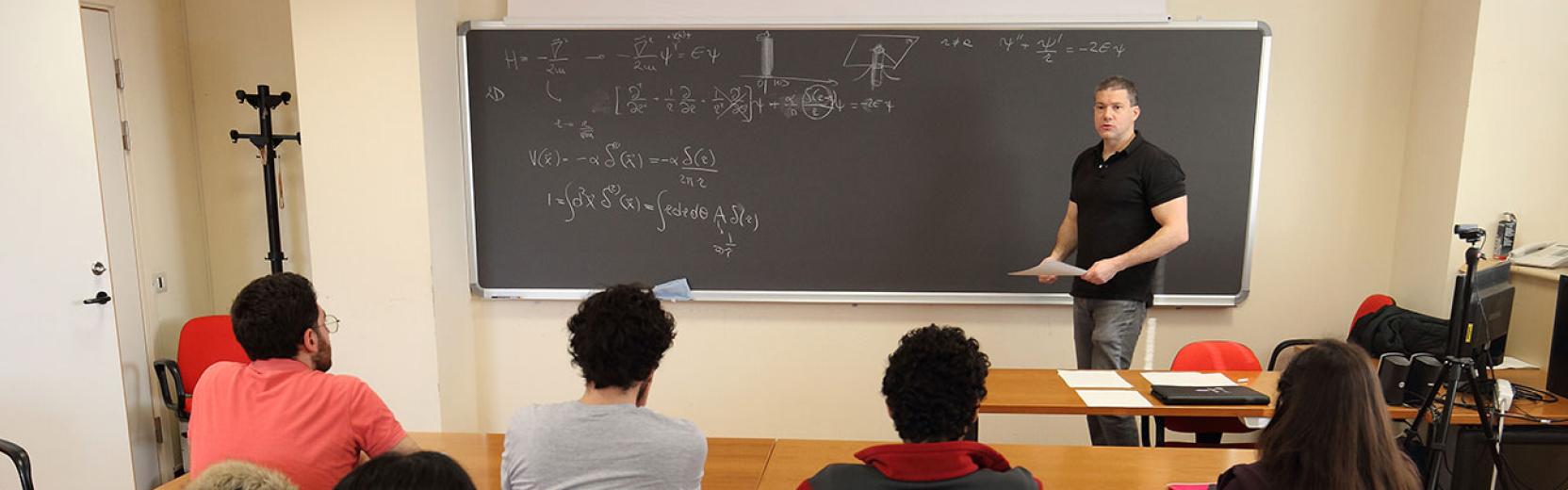

At the Dirac Medal ceremony, the medallists gave lectures (Kibble on "Symmetry Breaking and Defects in Physics and Cosmology", Peebles on "How Cosmology became Established Physics" and Rees on "Our Universe and Others") to a lecture hall packed with researchers and students, most of whom are attending ICTP's Summer School on Cosmology.

For more details about the Dirac Medal, visit its webpage.

A photo-essay with excerpts from an interview with the Dirac Medallists is available on Quotes and Reflections of the 2013 Dirac Medallists.