ICTP recently celebrated its 50th anniversary, but on a hill behind the campus there is evidence of life that's a million times older.

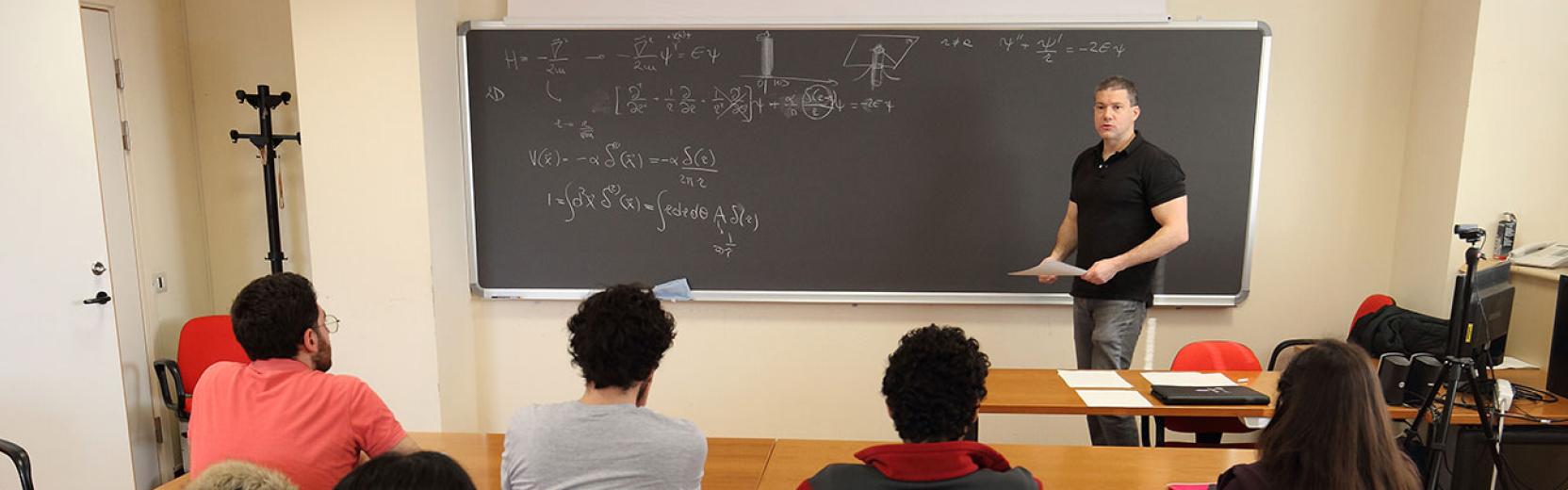

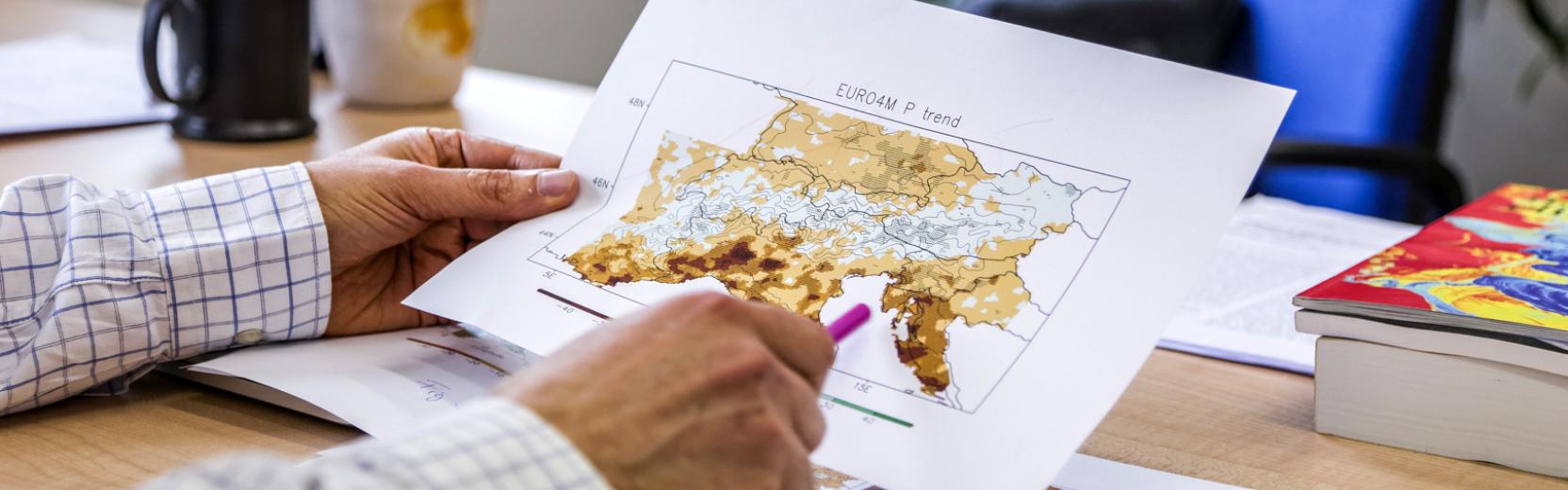

As part of the new seminar series in Quantitative Life Sciences, Andrea Baucon of the University of Milan and the UNESCO Geopark Naturtejo Meseta Meridional in Portugal presented a talk on ichnology, or the study of modern and fossil traces left behind by living organisms. Entitled "From worm burrows to dinosaur footprints," Baucon's talk explained how these traces can give scientists insights into the behaviour of ancient and modern organisms. Looking at footprints, for example, can indicate whether an animal was part of a herd or travelled alone and provide information on its speed and weight. In his research, Baucon uses quantitative techniques such as fractal geometry to analyse the traces he finds and determine what sorts of behaviours, such as foraging or gardening, they might represent.

"Traces are behaviours frozen in sediment," Baucon said. After providing multiple examples of such traces, from U-shaped burrows made by fish in the Adriatic Sea to South American fungi that grow on CD-ROMs, in the afternoon Baucon led a walk behind the former SISSA building on the ICTP campus to look for local examples of these traces. It didn't take long to find small holes and long, thin lines pockmarking a nearby sandstone wall -- the remains of burrows built beneath the sandy sea floor 50 million years ago.

The small group that admired the nearby ancient traces included members of ICTP's Quantitative Life Sciences group as well as researchers from the Multidiscplinary Laboratory. At the intersection of palaeontology, biology, earth science, and quantitative tools, ichnology is but one field that could benefit from the sort of quantitative life sciences research programme now underway at ICTP.